McNeil Island Historical Society

a 501(c)(3) non-profit charity

- Historic Sites

Welcome to Our Island

McNeil Island Historical Society (MIHS) promotes preserving the rich history of McNeil Island, WA., through positive use of it's existing structures and wildlife sanctions for the benefit of current and future generations. America's largest island prison from 1875 until it's closure in 2011, McNeil Island held not only convicts but also a vibrant island community starting with famous Oregon Trail pioneer Ezra Meekers' arrival in 1853. Logging, farming, boating, bootlegging and brothels all occurred while the rugged pioneer settlers held sway. The Federal and State prison staff and their families, also enjoyed the mystique and serenity of scarcely populated, highly restricted McNeil, which now houses America's most Unwanted - civilly convicted Sexual offenders who have served out their criminal terms but are unfit to return to society.... All this drama against the breathtaking backdrops of the Olympic Mountains, Mt. Rainier, and the Cascade Range, is too unique and beautiful to belong to only a few. Much better use should be made of the buildings designed by National Register Architects and created by convict crews. The MIHS is about the past and the potential of McNeil Island. Enjoy our site!

Currently this site is under construction. Updates will be published as the site is developed and the island archives grow. Please check back again soon for the latest information.

- Our book is now available at Amazon! Authored by our own Ann Kane Burkly and Puget Sound journalist Steve W. Dunkelberger, and published as part of Arcadia Publishing's Images of America series, McNeil Island presents a pictorial history of life on the island for residents and inmates alike, from the time of the original settlers through the era of the territorial, federal, and state prisons.

- Washington State Historical Society has won a prestigious national award for the McNeil Island Prison exhibit! Read the press release .

Copyright @ McNeil Island Historical Society . All rights reserved.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

- Photo Gallery

Front door of the administrative building on McNeil Island

The original powerhouse/power plant, dating back to the early 1900s, still stands on the island.

A 1907 cellhouse remains on the island with the 1920 extension that added a check-in booth for staff.

A 1907 cellhouse remains on the island.

Among the more famed inmates once incarcerated on the island, while under federal control, were Robert "Birdman of Alcatraz" Stroud and Charles Manson.

The facility's corridors were used as a setting in the 1989 film "Three Fugitives."

The Chapel of Mount Tahoma, an interfaith religious center, was built and completed in 1963 by the incarcerated population on the island and funded by the community.

The Chapel of Mount Tahoma included a choir loft for participating inmate choir singers.

The mural in the common dining hall shows a serene, abstract mountain view. The walkway for patrolling officers can be seen on the upper left and right sides of the dining hall.

The original programming building stands with construction dating between 1926 and 1936.

A view from inside the original programming building.

One of the rooms in the original inmate programs building still has sound-proofing wall covering from when it served as a music room.

The dairy and ranch operations on the island that offered self-sustaining agricultural products.

A view of the Puget Sound from the Superintendent's window.

The former McNeil Island superintendent's house.

The former multi-purpose community building sits with the former school classroom in the right wing of the building, the community center in the middle, and the chapel in the left wing of the building. There was a small bowling alley in the rear of the building available for weekend play and small tourneys for the workers and their families.

An abandoned former correctional officer house.

McNeil Island History

McNeil Island 1890

See Photo Gallery

NOTICE: There are no public tours offered of McNeil Island.

In 1841, McNeil Island, an island west of Steilacoom, Wash. and north of Anderson Island, was named after William Henry McNeill , captain of the Hudson Bay Company steamers 'Beaver,' 'Llama,' and 'Una.' A map recording error accounts for the difference in spelling, which was never corrected. In 1853, Ezra Meeker settled on McNeil Island and sold the property in 1862. Meeker’s homestead house was located in the area of the main correctional facility yard.

1875-1976: Federal Penitentiary

1981-2011: state correctional facility, 1998-current: special commitment center.

On January 22, 1867, Congress authorized the establishment of a territorial jail in the Washington Territory. On September 17, 1870, the Federal Government purchased 27.27 acres on McNeil Island for a federal prison, which officially opened in 1875. These 27 acres are the site of the main penitentiary complex.

The original McNeil Island cellhouse was built in 1873. In November 1874, the penitentiary was placed under the direction of the United States Marshal. Eight U.S. Marshals served in Washington Territory prior to statehood, and it was during Charles Hopkins’ tenure that the McNeil Island territorial prison opened on May 28, 1875. By the end of that year, the total prison population was nine.

In 1889, Washington was admitted to the Union. The first warden at the federal McNeil Island Penitentiary was Gilbert L. Palmer in 1893. The total custodial force consisted of seven guards.

In 1904, Attorney General Philander C. Knox was placed in full charge of the jail and McNeil Island was immediately declared an official United States prison. In 1927, an additional 67 acres were purchased for a prison farm to produce vegetables and fruit. Due to the need for water, another 1,618.33 acres were purchased in 1931. This brought the total prison acreage to 2,107.3, just less than half the island's 4,445 acres.

In 1934, the federal farm camp (North Complex) was completed. By 1947, the population was 320 inmates. At one time, the island provided for itself by raising vegetables, fruit, pork, beef, and milk. The final land transaction in 1940 involved 2,303.1 acres. The entire island, roughly seven square miles, was now under federal control. In 1944, Butterworth Lake was formed. In 1948, construction began on the community center and school to provide education for the children residing in the 52 homes on the island. School was held for the first time in 1952-53.

Well-known inmates that served at least part of their sentence in the McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary were Robert “Birdman of Alcatraz” Stroud from 1909 to 1912 for manslaughter, and Charles Manson from 1961 to 1966 for federal check forgery.

Due to high operational and maintenance costs and needed renovations, in 1976, the Federal Bureau of Prisons declared as “obsolete” the aging federal penitentiary on McNeil Island and decided to begin shutting it down. Washington’s need for additional prison space prompted state officials to explore the possibility of acquiring the prison to house state prisoners.

In 1981, the state signed a lease with the federal government granting the state use of the penitentiary. In April 1981, the Washington Department of Corrections began moving inmates into the newly renamed McNeil Island Corrections Center (MICC). Inmates were put to work fixing and improving the facility, which had not been maintained during the later years of federal operation. In 1984, the seven square mile island was officially deeded to the state of Washington.

In 1990, the Legislature appropriated $392 million to expand MICC, and by 1993, the Department of Corrections had built five new medium-security residential units, each housing 256 inmates, and a sixth segregation unit with 129 single cells. The original cellblock was demolished and replaced in 1994 with an inmate services building housing a hospital, educational center, recreation room, hobby shop, music room, and gymnasium.

In 1993 the balance of the island, 3,119 acres, was deeded to the Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife (DFW) for continuing use as a wildlife refuge. Wildlife agents are generally on the island once a week to monitor wildlife. Their boats also occasionally patrol the beaches. The land deeded for DOC use is in 24 separate parcels. Some parcels are about 100 acres, and some only two or three acres. For example, DOC land includes acreage for the minimum and medium facility complexes, but almost none of the beaches or Butterworth Lake. DFW is responsible for management of all island wildlife. A new deed to McNeil was issued in 1996, from the Department of Justice. All other original deed covenants continued, i.e., maintaining the federal graveyard, public access limitations, protection of wildlife, etc.

In April 2011, the oldest prison facility in the Northwest and final island-based prison in the nation was officially closed after 136 years.

2013-Current: Operations & Maintenance

The Department of Corrections’ Industries program, per the state’s 2013 budget bill, remains responsible for marine operations, wastewater treatment, water treatment, road maintenance, and other general island maintenance for the state to remain in compliance with the federal deed to McNeil Island. Site specific maintenance operations for the Department of Social and Health Services' Special Commitment Center is excluded.

In 1998, the state legislature authorized the placement of the state’s Special Commitment Center , a total confinement facility for sexual predators, on McNeil Island. The center, operated under the control and direction of the Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) , is a place where chronic and violent sex offenders can be civilly committed, per a court’s determination and after the end of their prison sentence. The DSHS remains responsible for facility maintenance and capital repairs of the Special Commitment Center.

Source: HistoryLink.org Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History, "McNeil Island Corrections Center, 1981-Present" by Daryl C. McClary ( www.historylink.org ).

- McNeil Island Habitat Restoration Project Feasibility Report (pdf)

- McNeil Island Shoreline Restoration

A Rare Look at the McNeil Island Prison

Less than three miles from the beaches of Chambers Bay lies one of the most unfamiliar and inaccessible places in all of Washington State. This is the Alcatraz of the Puget Sound.

Unless you were a prisoner, a guard, or a family member of either, it’s unlikely you’ve ever seen the island up close. Over the last year, the Washington State History Museum and KNKX Public Radio made several visits to the island in order to share its little known stories.

Unlocking McNeil’s Past: The Prison, The Place, The People brings together a collection of stories and artifacts from the prison’s 143 year history. As with much of history, it was written by those in positions of power. The exhibit takes this into account and invites people to consider the stories and voices of those who are not represented.

The McNeil Island Corrections Center officially opened in 1875 but had previously been used as a territorial prison while the rest of the island was inhabited by homesteaders. At various times throughout its history it held draft resistors and conscientious objectors from all of America’s wars, including 85 Japanese citizens who resisted the draft to protest their wartime confinement. It was also used multiple times as an immigrant detention center from the 1880s through the 1980s.

The prison was inhabited by Robert Stroud (aka Birdman of Alcatraz ), Frederick Peters, who impersonated Theodore Roosevelt and other celebrities in the early 1900s, Roy Gardner, a train robber who escaped three times before being sent to Alcatraz, several local bootleggers and gangsters, and Charles Manson in the early 1960s.

Artifacts in the exhibition range from the 2,000 pound wrought iron entry gate to a delicate violin made in secret by a prisoner from scavenged bits of wood. Different eras of the prison are separated by walls. The transitional spaces between each section are constructed according to the cell size of that era.

The last section is occupied by the photography exhibition Reclaimed . These photos document the current state of the island and its slow but steady return to nature. The narrated stories of former inmates and guards are amazing, the artifacts are impossible to forget, and the look into what life was like for the kids growing up on the island is unlike anything you’ll ever hear.

To get the entire story be sure to listen to the accompanying six-part KNKX podcast, Forgotten Prison .

The exhibition runs until May 26th. The museum will also host a symposium on March 2nd that discusses the challenges and opportunities of re-entry to society after incarceration. There will be a facilitated tour of the exhibit following the discussion.

The prison on McNeil Island officially closed in 2011. The island is now home to the Special Commitment Center for “sexually violent predators.” As of 2017, there were 268 residents at the facility. The island and its abandoned neighborhoods are also occasionally used for training by soldiers and airmen stationed at JBLM.

Historic photos courtesy of Washington State Historical Society and Tacoma Public Library’s Northwest Room.

I enjoyed reading the material here. The photos were and are helpful. What I am looking for are photos of the island, the federal prison, the settlers homes that were used by the correctional officers for family homes, the 2 room school house, the general store, center hill, officers row. My family lived on McNeil Island from mid 1847 until late 1953. My brother and I went to the two room school house. The last few months we lived there I went the Harriet atsylor a elementary school, that opened during the summer of 1953. Any advice or assistance you can proved would be greatly appreciated.

You should get in touch with the Washington State Historical Society. They did a huge amount of research for that exhibit and if any photos exist, they’ll probably know where to find them.

Look at a video on YouTube called “Forbidden Island” Vagrant holiday goes through a few houses and the school.

Love the island Regent blatmann was my crew boss I did 4 month drug possession

Coolest boss ever. Love that place lol

As a former inmate released a year prior to its closing this was the best prison I had been to, I would love to be able to go into it since it’s closed to look at the old cell blocks that were closed off to inmates. Wish I had a boat to get close up pics of the prison.

You were released the same year as my uncle. I am writing a book about his experience. Would be interested in chatting with you. In fact you were released in 1978.

looking for lists of registered inmates in early 1950’s and any information about them.

You should check with the Washington State Historical Society. They did a huge exhibit on McNeil Island a while back.

Really interesting as I just was sent by ancestry about photos etc; regarding my Grandfather who he and his brother were incarcerated there during prohibition for boot legging. Ironic the last name is Hartman like Sarah Hartman posting here. Don’t think we are related but would like to see how to find that info on him and his brother outside of using ancestry.

How about bussing the homeless to McNeil Island? There are many unused buildings there. Only 214 sexual deviants are housed there. It has been abandoned since 2011. Give them jobs working around the island. Make them grow their own food. Get our beautiful city back in return. I’m serious.

Around 1969, my Father, the Chief of Mechanical Services at the U.S. Penitentiary, Terre Haute, IN was offered a promotion and transfer to USP McNeil Is as associate warden. He was a construction expert and I’m sure the Bureau of Prisons wanted his expertise to either renovate, construct or tear down some aspects of the institution. When my Mother was asked about transferring, she put her foot down with a resolute “no”. During the post-WWII period the perception among career Bureau of Prisons personnel was one of adventurous, Puget Sound living on a island more self-contained than one would imagine e.g. school, store, etc. As our world modernized, the perception changed to stories of terrible isolationism, inconveniences and wives throwing groceries into the Sound from the launch after “losing it”. In 1969 USP McNeil was on the short list of institutions considered quite undesirable for employee families. I never got the opportunity to make that judgement for myself.

Does anyone know what N.M.S.T.A. Or. NMUSA. Might be as a crime. This is listed under my grandfather. He was there less than a year in the 1930’s

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Email List Sign-up

- What is Humanities Washington?

- Our Board of Trustees

- Financials and Governance

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Statement

- Host Prime Time Family Reading

- Host Prime Time Preschool

- Prime Time Program Resources

- Current Speakers

- Host a Speaker

- Host Resources

- Opportunity Grants

- Washington Stories Fund Grants

- Think & Drink

- Past Poets Laureate

- Center for Washington Cultural Traditions

- Public Humanities Fellows

- The Humanities Challenge

- Media Projects

- Get Involved

- Planned Giving

- In the News

- Press Releases

McNeil Island: Remembering a Forgotten Prison

An exhibit and podcast explores the Alcatraz you’ve never heard of—and it’s here in the Pacific Northwest.

- January 28, 2019

- News & Notes

- By Hannah Schwendeman

Before Alcatraz, there was McNeil Island. This tiny island in Puget Sound, a mere 11 miles from Tacoma, is home to the oldest prison in the Northwest. But you’re not alone if your first reaction is, “Why have I never heard of this place?”

Built before Washington even became a state, the McNeil Island Penitentiary stood for 136 years as a prison, and its relative isolation made it a little-known entity. Yet, according to Gwen Whiting, lead curator with the Washington State Historical Society, “no other prison represents as many different eras in incarceration history as McNeil does.” When McNeil closed in 2011, it was the last remaining island prison in the United States.

In a new exhibit, “ Unlocking McNeil’s Past: The Prison, The Place, The People, ” the Washington State Historical Society explores the stories of this often-forgotten island and its rich history. Humanities Washington supported the exhibit through a Washington Stories Fund grant. The museum is also partnering with KNKX to produce a podcast, Forgotten Prison , which just aired its first episode.

Among those stories is that of Howard Scott, who was incarcerated at McNeil Island due to his moral and religious objections to World War II. A close friend of anti-internment activist Gordon Hirabayashi (who was also imprisoned at McNeil), Howard became a conscientious objector following Executive Order 9066, which authorized the internment of Japanese-Americans.

While at McNeil, he met another prisoner who knew how to make violins. Although Scott had never learned to play, he was fascinated with the instrument. Using scrap lumber found in the yard, the man taught him how to heat wood on a radiator so he could turn it and shape it, slowly forming the pieces into the beginnings of a delicate instrument.

Eventually, his teacher was released from McNeil, leaving Scott to finish the project himself. His wife found a violin manual and began to copy instructions for him, including them in her daily letters to her husband. At first, the diagrams were confiscated by prison guards, so she became more creative. When visiting Howard with her baby, she hid the instructions between their newborn’s plastic pants and diaper or smuggle the plans in through her diaper bag. When Scott left McNeil, he was allowed to take the pieces he had already made, as well as the tools he handcrafted, home with him. Years later, his grandson had the violin assembled. The violin, Scott’s tools, and the letters are on display in the exhibit.

Another part of the exhibit highlights Fathers Behind Bars, a group created at McNeil who worked with a ministry to create a children’s book, Where My Dad Lives, describing their experience as incarcerated parents. Published in 2000, Where My Dad Lives answers children’s questions like: What does your dad do during the day? What does he eat? What can you do while you’re visiting him? Why is he in prison? Told from their own perspective, these fathers wanted to remind young readers of the importance of making good choices, so they could lead different lives than their dads. The couple who founded the ministry that began this project mortgaged their home in order to be able to publish enough copies of the book—they wanted to ensure that every child who visited their father at McNeil had one.

“Just by making McNeil visible, we are helping people think about [incarceration],” says Julianna Verboort of the Washington State Historical Society. “Because for many people, if you don’t have any experience with prisons, you don’t really think about that experience from the inside . . . We tend to push that out of our daily consciousness. By talking about the story of the prison and the fact that geographically, it’s right here, we’re making it very present for people.”

To Learn More

Visit the Washington State Historical Society’s exhibit, Unlocking McNeil’s Past: The Prison, The Place, The People , running January 26 to May 26.

Listen to the accompanying podcast, Forgotten Prison , produced by KNKX.

Attend a panel discussion March 2 on the experience of incarceration and re-entry, which will include our own Speakers Bureau presenter Omari Amili. Find out more on the museum’s events page .

Share This Post

- Category: News & Notes

- Tags: History , Mass incarceration , McNeil Island , prison , washington state

Get the latest news and event information from Humanities Washington, including updates on Think & Drink and Speakers Bureau events.

- First name *

- Last name *

- How did you hear about us?

- We hate spam as much as you do. Prove that you're not a spambot. What's 5 + 2? *

Iñupiaq men in qayaqs, Noatak, Alaska, circa 1929. Edward S. Curtis Collection, Library of Congress Digital Collections.

Crossing the Chilkoot Pass, circa 1898. Courtesy Candy Waugaman and Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park.

The Gold Rush boomtown of Nome on the Seward Peninsula, 1900. Courtesy of U.S. Geological Survey Photographic Library.

Unlocking McNeil’s Past: The Prison, The Place, The People

The exhibition presented the larger history of McNeil Island as a place, and the prison that opened there 143 years ago. The prison operated far longer than the better-known Alcatraz island prison. When the state’s correctional center on McNeil Island closed in 2011, it was the last prison in the nation only accessible by air or water.

From its beginnings as a territorial prison through its tenure as a federal and state penitentiary, the story of McNeil illuminates how incarceration in the U.S. has changed over time, as seen through the evolution of the prison facility, itself.

Unlocking McNeil’s Pas t: The Prison, The Place, The People presented history through accounts from prison staff, inmates, and residents of the island. It explored McNeil’s connections to significant state and national events. It examined the evolution of prison practices through territorial, federal, and state lenses, as well as the physical landscape of the prison itself and how its structure reflected these changes. Stories of early settlement and the unique relationship between the prison and its island community were also shared through this exhibition.

Listen to the six part podcast Forgotten Prison created in collaboration between KNKX.org and Washington State History Museum.

The forgotten prison podcast was supported through a storytelling grant from humanities washington ..

- Alaska's Historic Canneries

McNeil Island’s Past and Present

Other items that may interest you

Eerie Remains of WWI History Are Lurking in Henderson …

The many names of filucy bay: a saga told and a …, the storyteller and the princess: the mystery of …, early settlers on the key peninsula: the dawn of the ….

UNDERWRITTEN BY THE FUND FOR NONPROFIT NEWS (NEWSMATCH) AT THE MIAMI FOUNDATION, THE ANGEL GUILD, ADVERTISERS, DONORS AND PEOPLE WHO SUPPORT INDEPENDENT, NONPROFIT LOCAL NEWS

The Spectator

The Complex Legacy Of Washington’s Mysterious Island Prison

Sam Bunn , Investigative Editor | May 31, 2023

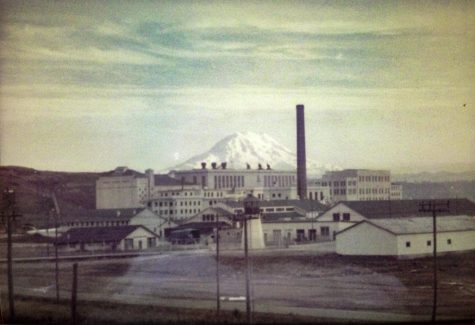

Image courtesy of the McNeil Island Historical Society.

The McNeil Island Corrections Center, previously known as USP McNeil Island.

The following article contains discussion of sexual offenses, including crimes against children.

Situated in the Southern reaches of the Puget Sound, the 6.6 square miles of McNeil Island looks uninteresting, just like any of the hundreds of islands off Washington’s west coast. It’s not immediately obvious that the government owns every inch of it and that boats are not permitted to come within a hundred feet of the shoreline, nor that a prison established there nearly 150 years ago predates not only the federal penitentiary system, but the state itself. Perhaps most unusually, the only residents of the island today are Washington’s most dangerous sex offenders, locked away from the public in a unique legal limbo.

McNeil Island was first purchased by the U.S. government in 1875, and a territorial jail was established on its shores. In 1891, the Three Prisons Act was passed, making McNeil officially a government facility and by some measure the first federal prison in the U.S.. Chris Wright, communications director for the Washington State Department of Corrections (DOC), described the advantages of having a prison that was accessible only by sea.

“It’s like Alcatraz—it’s a lot harder for somebody outside of the walls to get off the island,” Wright said. “It adds another security element.”

Notably though, McNeil Island is huge— thousands of times larger than Alcatraz . Because of the size and isolation, inmates were allowed more freedom than most prisons of the era and were encouraged to learn trades as diverse as leatherwork, shipwrighting and floral arrangements. They existed in close proximity to correctional staff and their families, who lived on the island in a miniature community.

“There was a school, there was a warden mansion,” Wright said. “It was a very unique environment where people were living, working and raising their kids.”

Ann Kane Burkly is the president of the McNeil Island Historical Society and grew up on the island she now works to preserve.

“I lived on the top of the hill and you could look one way towards the Sound and see Anderson Island and Steilacoom and the other side you were looking out at the Olympics. We clammed and fished—anything you can possibly do outdoors,” Burkly said. “There were deer everywhere, coyotes, a bear, a cougar. Raccoons were everywhere because the inmates loved them and would feed them…it was wonderful to grow up there.”

While living a stone’s throw from a prison could have been a dangerous proposition, island life produced a relationship of sorts, even between inmates and the families of correctional staff who resided around them.

“We were never afraid,” Burkly said. “Inmates in some instances were quite kind and protective of us. There’s a code in prison—they don’t like anybody who messes with kids.”

In 1976, the Bureau of Prisons announced that McNeil would be phased out. The prison was old and built to house thousands of inmates, a dinosaur in an era where the prisons were designed to be small, with capacities of five hundred or less. On top of that, the cost of island upkeep was a continual sink on the federal budget. But as the shutdown began on McNeil, Washington was experiencing an overflow of prisoners at the state level, attributable in significant part to the rise of the War on Drugs .

“[The U.S. Government] thought they were going to smaller prisons with Supermax surveillance,” Burkly said. “But instead we had the eighties come along with the three strikes law and prisons grew massively.”

Former Governor John D. Spellman saw a solution in the facilities already available offshore, and leased the island from the federal government in 1981. The facility would stand for nearly 30 additional years as a state prison before being condemned for much the same reason—it was too old, too big and too expensive.

“2008 was one of the worst financial crises in state history,” Wright said. “Large cuts were made everywhere and that’s when it was officially decided that [McNeil] was too pricey.”

With the closure, the small village on McNeil that once held a thriving community was left to fall apart. Burkly, who still returns to the island from time to time, sees her childhood home, schoolhouse and the rest of the island that raised her slowly succumbing to mold and decay.

But that wasn’t quite the end of McNeil Island. The Department of Social and Human Services (DSHS) built another facility on the island in 2004, deemed the Special Commitment Center (SCC) . The facility is not technically a prison, but nonetheless patients are not permitted to leave.

Normally, confinement after one’s prison sentence has ended would be a violation of a citizen’s civil rights. But due to a Washington State’s Community Protections Act, passed in 1990 , a judge can civilly commit someone convicted of a sex offense to a treatment facility for an indefinite length of time.

Brad Meryhew, a criminal defense attorney and chair of Washington’s Sex Offender Policy Board, described the law as a public health and safety measure.

“We as a society have confined people against their will outside of the criminal justice system for most of our history, for what we deem to be profound mental illness,” Meryhew said. “If somebody is a danger to themselves or to others, or if that person is gravely disabled…the State has the right to take them into civil commitment.”

The isolation of McNeil, which had driven the federal government and the DOC off the island, was almost a benefit as the location of a treatment center for sex offenders. Tyler Hemstreet, media relations manager with the DSHS, pointed out that an offshore facility helped the public feel more secure than mainland treatment by sequestering offenders an ocean away.

“When [SCC patients] are on McNeil, they’re out of sight, out of mind,” Hemstreet said. “And I think community members like it that way.”

The number of people civilly confined at McNeil is not publicly available, though past articles have put the number north of 200. The majority of patients stay at the SCC for decades, with the island also serving as pretrial holding for ex-cons awaiting a hearing on if they are to be officially civilly committed. Hemstreet described an extreme case of a current resident confined at the SCC for seven years, still awaiting his trial. Many of McNeil’s residents will die on the island.

Some will take a different path. If treatment has been completed and a court finds the individual to no longer be a community risk, patients can be released to a stage called Less Restrictive Alternative (LRA), in which they are allowed to return to the community in a limited capacity. Residents of Tenino and Enumclaw have vehemently opposed establishing LRAs in their cities, though Hemstreet emphasized that community risk is minimal.

“They not only have DOC oversight with ankle bracelets and attorneys, but they also have community treatment providers and stable housing. They have intense wraparound services that strengthen community safety and minimize the likelihood of reoffense,” Hemstreet said.

The process of civil commitment has faced ethical and legal challenges. A 2015 complaint lodged by Disability Rights Washington asked the state to make a true rehabilitative effort at the SCC, alleging that many residents were being denied access to therapy that would allow them to make progress towards release.

“The point was made that you couldn’t simply warehouse these individuals,” Meryhew said. “You had to offer them meaningful treatment and opportunities.”

But offering sex offenders rehabilitative therapy and the ability to return to the community is a highly controversial topic. Generally speaking, many Americans believe in a severe legislative approach to sex crimes. Stronger laws and stricter punishments often pass with bipartisan support, and opposition on any grounds can be construed as excusing horrific abuse . Capital punishment is frequently part of the conversation, with a Florida law designed to streamline the execution of certain sex offenders enacted earlier this month.

Meryhew argued that the instinct to enact vengeance on those who have done harm doesn’t always reflect the reality of the situation.

“The truth is, [some long-term SCC patients] are no longer sexually violent predators,” Meryhew said. “We can now say, with some degree of psychological certainty, that these people are not the risk to the community that they were when they were first brought into the system.”

An alternative to the increasingly severe punishments, medical experts are pushing for therapeutic treatment. Fred Berlin is the director of the National Institute for the Study, Prevention and Treatment of Sexual Trauma, as well as the director of the Sex and Gender Clinic at Johns Hopkins University. Berlin has been researching paraphilias for nearly 50 years, and believes that a treatment-focused approach is more effective than a punitive one, even for the most heinous crimes.

“Take the example of someone who’s sexually attracted to children. There’s nothing about prison alone that can erase those attractions or enhance that person’s capacity to resist acting on them,” Berlin said. “The idea that we can punish the problem or legislate the problem away is very naive.

Therapeutic treatment for sex offenders in the U.S. (including the SCC and McNeil Island) is reactive in nature, occuring only after somebody has been victimized. Berlin pointed to a German program, Prevention Project Dunkelfeld (PPD), as a treatment model that hopes to stop offenses before they are committed. PPD guarantees therapy for pedophiles and hebephiles, and is only possible because of unusually strong doctor-patient confidentiality laws in Germany.

“There have been reports… of very significant numbers of previously undetected people coming in, getting help, and doing well,” Berlin said. “We can’t do that in the United States…there are a number of young men who are aware they’re not attracted to people their own age and want help, but the last thing they’re going to do is raise their hands and ask for it.”

For over a hundred and fifty years, McNeil Island has served to punish people who have committed the most grievous wrongs against others. But it’s also been a place of healing and rehabilitation for society’s most downtrodden, with prisoners and patients released better than the island found them. Burkly views McNeil’s legacy as one of healing, not one defined by the horrors of the prison industrial complex.

“You spend a lot of time looking inward and growing [at McNeil],” Burkly said. “People are recoverable if you give them an opportunity and some guidance.”

What comes next for McNeil Island is a hotly debated topic with numerous interested parties. The Historical Society advocates for the preservation of the old prison facilities and the island village that is fighting an onslaught of decay. The Steilacoom tribe claim the beaches as part of their hunting grounds. Real estate moguls are eyeing the undeveloped beauty of McNeil, while the Department of Fish and Wildlife works to return the island to its natural state.

In the meantime the DSHS continues to operate the SCC, hoping to find recovery and restoration for a population reviled by policymakers, healthcare officials and the public.

“There’s not the sense that the people that are out there at McNeil Island are human beings deserving of help,” Berlin said.

Seattle University's student newspaper since 1933

- Work at The Spectator!

Comments (1)

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Terry Akins Jan 11, 2024 at 1:59 pm

There is a happy medium there. I gaze at the island from my home every day and wonder why we have set aside such a valuable asset for so little gain. The efforts of the state to rehabilitate the “residents” could continue to take place within a more developed environment. The idea that we must separate ourselves just to provide security really doesn’t make sense. Hopefully, the future will see a legislature with a more imaginative approach.

Log in and send us updates, images and resources

McNeil Island Circumnavigation

Paddle around an island in South Puget Sound that was a federal prison, then a state prison, and now a state commitment facility for sex offenders. No landing on the island is permitted, making this a potentially more challenging sea kayak trip.

launch points

- The 72nd St Boat Lunch on Key Peninsula . There's nothing but a boat ramp here.

- Penrose Point State Park . Restrooms are available here.

- Steilacoom Ferry . Parking at the ferry terminal parking area that accepts only credit cards. Restrooms available inside the passenger building. The boat ramp is adjacent to the building.

on the water

McNeil Island is wholly government owned. First a Federal and then State Prison, it is noa a State Commitment Facility for sex offenders. Learn more at on the Department of Corrections's McNeil Island History web page. Because of its restricted use, the shoreline is quite wild with a frequent seal haul-out on the island's northeast corner. Break points include Eagle Island State Park and the public shoreline along the Key Peninsula. Gertrude Island , while not part of the restricted McNeil Island facility, serves as a wildlife sanctuary. Kayakers tend to make only the briefest of visits and only when it is an island and not a Tombola.

- No landing is allowed on the island. Boaters must stay 100 yards from the shore and obey all posted signs. There are no bail outs on McNeil Island. You must be able to cross the channel regardless of conditions.

- The ferry is not available to unauthorized personnel, even in a medical emergency.

- Suitable Activities: Sea Kayaking

- Seasons: Year-round

- Weather: View weather forecast

- Difficulty: Sea Kayak III+

- Length: 15.0 nm

- Land Manager: Land Manager Varies

- Parking Permit Required: see Land Manager

- Recommended Party Size: 12

- Maximum Party Size: 12

- Maximum Route/Place Capacity: 12

- NOAA Puget Sound: Southern Part No. 18448

- MapTech Puget Sound Chart No. 100

There are no resources for this route/place. Log in and send us updates, images, or resources.

The Mountaineers

Helping people explore, conserve, learn about, and enjoy the lands and waters of the Pacific Northwest and beyond.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Mountaineer Magazine

Mountaineers Books

An independent nonprofit publisher

- Bookseller Info

- Press Inquiries

Connect with the Mountaineers Community

Connect with the mountaineers books community.

The Mountaineers®, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Tax ID: 27-3009280.

Mountaineers Books is a registered trademark of The Mountaineers®, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Tax ID: 27-3009280.

- Environment

Video | McNeil Island tour

Former McNeil Island residents Tim Taylor and Nancy Armstrong share memories of growing up on a small island with a prison.

Share story

Most read local stories.

- Stehekin residents prepare to defend their town as Pioneer fire nears WATCH

- Washington state primary election results 2024

- New rentable LimeGliders to arrive in Seattle next week

- Seattle air quality and wildfire maps: Active WA, PNW fires in 2024

- Franz, Dhingra concede primary defeat in U.S. House, AG races

Mcneil Island Offers Prison Tours

MCNEIL ISLAND - Public tours of the state's correction center here, once a federal prison holding some of the nation's toughest felons, will begin next month.

Two tours a month for up to 20 persons at a time are scheduled, lasting about four hours each, a center spokesman said.

Interested persons should call Rick Jordan at 253-512-6583 or Nai-Jeanne Busick at 253-512-6602. Dates for the November tours were not released.

An official website of the United States government, Department of Justice.

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

NCJRS Virtual Library

Mcneil century - life and times of an island prison, additional details.

Steven Long , 111 North Canal Street , Chicago , IL 60606 , United States

No download available

Availability, related topics.

How about sending homeless folks to live on McNeil Island? The TNT examines the question

F inding places to operate shelters and stability sites to serve homeless people has proved challenging for Pierce County governments, which often run into opposition from people who don’t want such facilities in their neighborhoods.

A recent suggestion likely would minimize such opposition.

“We’ve had the homeless problem forever, and one of the best ideas I ever heard was to take McNeil Island and make that a place for our homeless to be,” a Gig Harbor resident told the Pierce County Council on July 9.

The woman testified in a council chamber filled with representatives from homeless service providers there to advocate for a policy that would make it easier to establish temporary shelters and tiny home villages for the homeless.

McNeil Island is in Puget Sound, west of Steilacoom and north of Anderson Island. It has long served as home for federal or state detention centers of some variety.

While the providers seemed to smirk and scoff at the woman’s suggestion, it’s not the first time someone has brought up using the island as a place to build facilities for the homeless.

While on the campaign trail in recent months, Republican gubernatorial candidate Dave Reichert pitched using the island to house the homeless .

Recently, McNeil Island was on a list of properties the county’s Human Services Department was considering to host a $2.5 million stability site to serve as an emergency homeless shelter.

Ultimately, the county decided the island was not an ideal fit for the stability site. A spokesperson for the county told The News Tribune the island is zoned for lower density, rural usages, has no sewer infrastructure and is only accessible via a ferry system operated by the Department of Corrections.

Would it work?

For more than 100 years, the island was known for a federal prison that held infamous convicts such as Charles Manson and Mickey Cohen. Beginning in 1981 that facility began to be used as a state corrections center. In 2011, the oldest prison facility in the Northwest was officially closed after 136 years.

The island now is home to the state’s Special Commitment Center, which is run by the state Department of Social and Health Services. The facility serves to rehabilitate sex offenders the state has defined as “sexually violent predators.”

A KOMO News documentary titled “Seattle is Dying” in 2019 suggested using the island’s decommissioned prison to house the homeless and provide wrap-around services such as substance-abuse therapy.

The prison, which is separate from the Special Commitment Center, is owned by Washington’s Department of Corrections (DOC). Chris Wright, a spokesperson for the DOC, said the facility was closed in 2011 and had been “mothballed” since then — empty and without staff.

Wright told The News Tribune the facility was “unusable,” with aging infrastructure, structural issues and asbestos, among other problems. He said he was not aware of any serious conversations about re-purposing the former prison.

“It’s not feasible,” he told The News Tribune in an email.

Rob Huff is a spokesperson for the Tacoma Pierce County Coalition to End Homelessness — a regional coalition of community organizers, service providers and government agencies that meets weekly to discuss efforts and programs to end homelessness.

Huff said he thinks the proposal to send individuals experiencing homelessness to an island usually comes from “folks who haven’t thought through the issue.” He said even if the island was an oasis with all the infrastructure and supportive services needed to help the unhoused, removing and isolating people would come with a “list of challenges.”

“For me, the solutions should be in the community they live in,” Huff said in an interview with The News Tribune.

He said folks living unhoused often need a job to get back on their feet, and being on an island comes with “obvious transportation issues.”

Huff said he understands that some people are frustrated by the homelessness crisis and made uncomfortable when they see people having to sleep on the street in the cold of winter, but political solutions that aim to get those living homeless “out of sight” are not the answer.

- Environment

- Health Care

- Police & Courts

- Election 2024

How about sending homeless people to live on McNeil Island?

By: cameron sheppard - august 7, 2024 12:42 pm.

McNeil Island, seen here, is located in the southern Puget Sound and is the site of state Department of Corrections facilities. (lfreytag/Getty Images)

Finding places to operate shelters and stability sites to serve homeless people has proved challenging for Pierce County governments, which often run into opposition from people who don’t want such facilities in their neighborhoods.

A recent suggestion likely would minimize such opposition.

“We’ve had the homeless problem forever, and one of the best ideas I ever heard was to take McNeil Island and make that a place for our homeless to be,” a Gig Harbor resident told the Pierce County Council on July 9.

The woman testified in a council chamber filled with representatives from homeless service providers there to advocate for a policy that would make it easier to establish temporary shelters and tiny home villages for the homeless.

McNeil Island is in Puget Sound, west of Steilacoom and north of Anderson Island. It has long served as home for federal or state detention centers of some variety.

While the providers seemed to smirk and scoff at the woman’s suggestion, it’s not the first time someone has brought up using the island as a place to build facilities for the homeless.

While on the campaign trail in recent months, Republican gubernatorial candidate Dave Reichert pitched using the island to house the homeless.

Recently, McNeil Island was on a list of properties the county’s Human Services Department was considering to host a $2.5 million stability site to serve as an emergency homeless shelter.

Ultimately, the county decided the island was not an ideal fit for the stability site. A spokesperson for the county told The News Tribune the island is zoned for lower density, rural usages, has no sewer infrastructure and is only accessible via a ferry system operated by the Department of Corrections.

Would it work?

For more than 100 years, the island was known for a federal prison that held infamous convicts such as Charles Manson and Mickey Cohen. Beginning in 1981 that facility began to be used as a state corrections center. In 2011, the oldest prison facility in the Northwest was officially closed after 136 years.

The island now is home to the state’s Special Commitment Center, which is run by the state Department of Social and Health Services. The facility serves to rehabilitate sex offenders the state has defined as “sexually violent predators.”

A KOMO News documentary titled “Seattle is Dying” in 2019 suggested using the island’s decommissioned prison to house the homeless and provide wrap-around services such as substance-abuse therapy.

The prison, which is separate from the Special Commitment Center, is owned by Washington’s Department of Corrections (DOC). Chris Wright, a spokesperson for the DOC, said the facility was closed in 2011 and had been “mothballed” since then — empty and without staff.

Wright told The News Tribune the facility was “unusable,” with aging infrastructure, structural issues and asbestos, among other problems. He said he was not aware of any serious conversations about re-purposing the former prison.

“It’s not feasible,” he told The News Tribune in an email.

Rob Huff is a spokesperson for the Tacoma Pierce County Coalition to End Homelessness — a regional coalition of community organizers, service providers and government agencies that meets weekly to discuss efforts and programs to end homelessness.

Huff said he thinks the proposal to send individuals experiencing homelessness to an island usually comes from “folks who haven’t thought through the issue.”

He said even if the island was an oasis with all the infrastructure and supportive services needed to help the unhoused, removing and isolating people would come with a “list of challenges.”

“For me, the solutions should be in the community they live in,” Huff said in an interview with The News Tribune.

He said folks living unhoused often need a job to get back on their feet, and being on an island comes with “obvious transportation issues.”

Huff said he understands that some people are frustrated by the homelessness crisis and made uncomfortable when they see people having to sleep on the street in the cold of winter, but political solutions that aim to get those living homeless “out of sight” are not the answer.

This article was first published by the Tacoma News Tribune through the Murrow News Fellow program , managed by Washington State University.

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.

Cameron Sheppard

Cameron Sheppard is a Murrow News Fellow covering homelessness in Pierce County and its intersections with public policy, housing, health and community.

Related News

COMMENTS

Welcome to Our Island. McNeil Island Historical Society (MIHS) promotes preserving the rich history of McNeil Island, WA., through positive use of it's existing structures and wildlife sanctions for the benefit of current and future generations. America's largest island prison from 1875 until it's closure in 2011, McNeil Island held not only ...

The original McNeil Island cellhouse was built in 1873. In November 1874, the penitentiary was placed under the direction of the United States Marshal. Eight U.S. Marshals served in Washington Territory prior to statehood, and it was during Charles Hopkins' tenure that the McNeil Island territorial prison opened on May 28, 1875.

This past exhibition was on view from January 26 to May 26, 2019. This exhibition presents the larger history of McNeil Island as a place, and the prison that opened there 143 years ago. The prison operated far longer than the better-known Alcatraz island prison. When the state's correctional center on McNeil Island closed in 2011, it was the ...

The prison on McNeil Island officially closed in 2011. The island is now home to the Special Commitment Center for "sexually violent predators.". As of 2017, there were 268 residents at the facility. The island and its abandoned neighborhoods are also occasionally used for training by soldiers and airmen stationed at JBLM.

When McNeil closed in 2011, it was the last remaining island prison in the United States. In a new exhibit, " Unlocking McNeil's Past: The Prison, The Place, The People, " the Washington State Historical Society explores the stories of this often-forgotten island and its rich history. Humanities Washington supported the exhibit through a ...

The exhibition presented the larger history of McNeil Island as a place, and the prison that opened there 143 years ago. The prison operated far longer than the better-known Alcatraz island prison. When the state's correctional center on McNeil Island closed in 2011, it was the last prison in the nation only accessible by air or water.

The McNeil Island Corrections Center, located in southern Puget Sound, 2.8 miles from Steilacoom, Washington, was the oldest prison facility in the Northwest. Built in 1875, it began as the first federal prison in the Territory of Washington. The federal government declared the prison obsolete in 1976 and began to dismantle the facility.

Press tour at the Washington State History Museum, 1911 Pacific Avenue, Tacoma, with WSHS and KNKX on Tuesday, January 22 at 11:00 AM. ... United States Penitentiary, McNeil Island, photographic print, cyanotype. Buildings of the U.S. Penitentiary on McNeil Island, WA, circa 1890-91. Looking out over Tacoma Narrows.

Noted pioneer Ezra Meeker homesteaded on the island in the mid-1850s before going off-island to found the City of Puyallup in 1862. Puget Sound was booming, and with the growing population came crime. The Washington Territory needed a prison, and McNeil Island seemed like a logical spot. The island became a territorial prison on May 28, 1875 ...

In 2011, the state closed the prison that predated its own statehood. Now, it's a ghost town filled with history on a 4,200-acre forbidden island.

Sources: Betsey Johnson Cammon, Island Memoir: A Personal History of Anderson and McNeil Islands (Puyallup: The Valley Press, Inc., 1969); Paul W. Keve, The McNeil Century: The Life and Times of an Island Prison (Chicago: Nelson-Hall Publishers, 1984); Edmond S. Meany, Origin of Washington Geographic Names (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1923); Murray Morgan, Puget Sound: A Narrative ...

McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary (1904-1981) Managed by: Federal Bureau of Prisons (1904-1981) Washington State Department of Corrections (1981-2011) County: Pierce County: State/province: Washington: Postal code: P.O. Box 88900: Country: United States: The McNeil Island Corrections Center (MICC) was a prison in the northwest United ...

The State Historical Society's newest exhibit takes a deep dive into the notorious 143-year-old McNeil Island Prison that shuttered in 2011.

United States Penitentiary, McNeil Island, Photographic print, cyanotype, circa 1890-1891. Interior of a cell block at the U.S. Penitentiary on McNeil Island, WA. Washington State Historical Society, Springer Family Collection, C2014.165.3. The prison's population steadily increased over the years and new cell houses were built to meet the ...

Situated off of the shores of Steilacoom, Washington, John learns what life is like on the only island operating prison since the closing of Alcatraz in 1963...

McNeil Island is an island in the northwest United States in south Puget Sound, located southwest of Tacoma, Washington.With a land area of 6.63 square miles (17.2 km 2), it lies in an area of many small, inhabited islands including Anderson Island to the south across Balch Passage; Fox Island to the north, across Carr Inlet, and to the west, separated from Key Peninsula by Pitt Passage.

Perhaps most unusually, the only residents of the island today are Washington's most dangerous sex offenders, locked away from the public in a unique legal limbo. McNeil Island was first purchased by the U.S. government in 1875, and a territorial jail was established on its shores. In 1891, the Three Prisons Act was passed, making McNeil ...

McNeil Island is wholly government owned. First a Federal and then State Prison, it is noa a State Commitment Facility for sex offenders. Learn more at on the Department of Corrections's McNeil Island History web page. Because of its restricted use, the shoreline is quite wild with a frequent seal haul-out on the island's northeast corner.

Former McNeil Island residents Tim Taylor and Nancy Armstrong share memories of growing up on a small island with a prison.

McNeil057. McNeil055. Named for Wm. A. Callahan, first superintendant of the state prison when the the federal prison was leased to the state in 1981. Ownership was transferred in 1984. The photos in this category are related to the federal penitentiary built on McNeil Island in 1875. Operation of the prison was turned over to the state in 1981.

The now-abandoned prison at McNeil Island ran for 136 years. That means the history of the place can tell us a lot about how prisons have changed over time. In Episode 3 of Forgotten Prison, hosts Simone Alicea and Paula Wissel introduce us to former McNeil inmates and guards, and take listeners through the abandoned structures on the island ...

MCNEIL ISLAND - Public tours of the state's correction center here, once a federal prison holding some of the nation's toughest felons, will begin next month. Two tours a month for up to 20 persons at a time are scheduled, lasting about four hours each, a center spokesman said.

1984. Length. 331 pages. Annotation. This book traces the history of the McNeil Island Federal Prison from its opening in 1875 to its transfer to Washington State ownership in 1981, with attention to the geographical characteristics of the area, the achievements of the various wardens, changes in prison programs, larger bureaucratic changes ...

For more than 100 years, the island was known for a federal prison that held infamous convicts such as Charles Manson and Mickey Cohen. Beginning in 1981 that facility began to be used as a state ...

McNeil Island is in Puget Sound, west of Steilacoom and north of Anderson Island. ... For more than 100 years, the island was known for a federal prison that held infamous convicts such as Charles Manson and Mickey Cohen. Beginning in 1981 that facility began to be used as a state corrections center. In 2011, the oldest prison facility in the ...