Embracing powerful nature and fragile ecosystems

By anna maría bogadóttir.

Over the course of a few years, the number of annual visitors in Iceland grew from half a million to two million. While the rapid growth surely benefited the economy, it came hand in hand with signs of over-tourism, causing red alerts and closures of popular nature sites due to excessive intrusion. While creative landowners responded to the situation by becoming tourist operators, the government launched a series of official plans, funding schemes and other initiatives. The aim was to coordinate research and prepare to develop physical and human infrastructure that would ease access to and protect the primary attraction: Nature.

Icelandic nature and tourism

In flux between glaciers and volcanoes.

Iceland is a volcanic island located in the North Atlantic Ocean, 300 km east of Greenland and 900 km west of Norway. The Arctic Circle runs through the island of Grímsey, 40 km north of mainland Iceland. Due to Iceland’s location, north of the Central Atlantic, its nature and ecosystems are particularly fragile.

Interactive Map

The surface area is 103,000 km², but most of the 376 thousand inhabitants live close to the coastline, spanning over 500 km. The population density is four people per km². Iceland’s landscapes are shaped by the forces of nature, varying from snow-capped mountains and staggering waterfalls, deep fjords and valleys formed during the ice age to vast volcanic deserts, black sand beaches, gushing geysers, natural hot springs, and lava fields as far as the eye can see. About 10% of the land area is covered by receding glaciers. Scientists predict that they may largely vanish in the next 100-200 years, which will drastically change the landscape.[1]

Iceland’s climate is subpolar oceanic, with cold winters and cool summers, although the winters are milder than in most places of similar latitude due to the Gulf Stream, which ensures a more temperate climate in Iceland’s coastal areas all year round. The Gulf Stream also results in abrupt and frequent weather shifts, which is why one may experience four seasons in one day. Iceland does not have a rainy season, but precipitation peaks from October to February, with the southern and western parts receiving the most rainfall. In the North, East and inland, there are colder winter temperatures but warmer summers and noticeably less snow and rain. Iceland’s most influential weather element is the varying types and degrees of wind.

The appeal and image of nature

For centuries, Iceland has been a destination for international scientists and artists aiming to study and experience volcanoes and glaciers as well as the Icelandic society and its culture. Fictive and real landscapes have served as the setting for narratives from Norse mythologies written in the 13th century, 18th-century travel journals, 19th and 20th-century adventure novels, and recent films such as Star Wars , James Bond, and Game of Thrones . Taken together, these narratives create a general idea of destination nature experiences, as is currently visually exhibited on Instagram and other digital platforms where the idea of the destination Iceland continues to be moulded by influencers.

Since the mid-twentieth century, Iceland has worked towards increasing the number of foreign visitors. It grew slowly during the 20th century up until the 1990s. A significant part of those who travelled to Iceland used to be experienced nature-lovers, geared with analogue maps and compasses, ready for camping and hiking in remote areas without any designated infrastructure. The visits grew steadily in the second half of the 20th century, with a total of four million foreign tourist arrivals from 1950 to 2000. After the economic meltdown in 2008, the Icelandic government increased its focus on tourism as a potential rescue line for foreign currency, with the Icelandic krona in free fall. Furthermore, the Eyjafjallajökull eruption in 2010 put Iceland on the map by bringing flight travel to a halt in large parts of the world. Fearing a negative impact on the country’s growing tourism industry, Iceland launched the most extensive tourism campaign to that date, called “Inspired by Iceland”[2]. However, the campaign proved somewhat unnecessary, as the eruption significantly increased interest in Iceland as a destination. In addition, the drop in the local currency made Iceland a less expensive destination and thereby in reach for a larger group of visitors than before. Hence, the tourist surge following the Eyjafjallajökull eruption came hand in hand with export-led economic recovery plans emerging from the 2008 financial crisis. This resulted in exponential growth in the number of foreign visitors. Whereas tourism doubled between 1997 and 2007, the number of tourists grew 500% between 2010 and 2017, peaking at 2.5 million in 2018[3]. The sudden increase was followed by a slight decrease in 2019 and a sudden stop in 2020, caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. A short sequence that could resemble a rollercoaster ride.

In spring 2021, the area of Geldingadalir metamorphosed into an accessible erupting volcano midway between Keflavik International Airport and the capital city of Reykjavik. Overnight, the priorly unknown area became a pilgrimage site for scientists and local and foreign visitors alike. Regularly on the news, geologists referred to measurements and monitoring to predict the future of the volcanic activities, all the while stressing that nature behaves in unpredictable and uncontrollable ways. In contrast, engineers presented their experiments and calculations for plans to control the lava flow. On one hand, nature was viewed as a force beyond human control, and on the other, a controllable phenomenon, a force to be tamed.

The right to nature and nature’s right

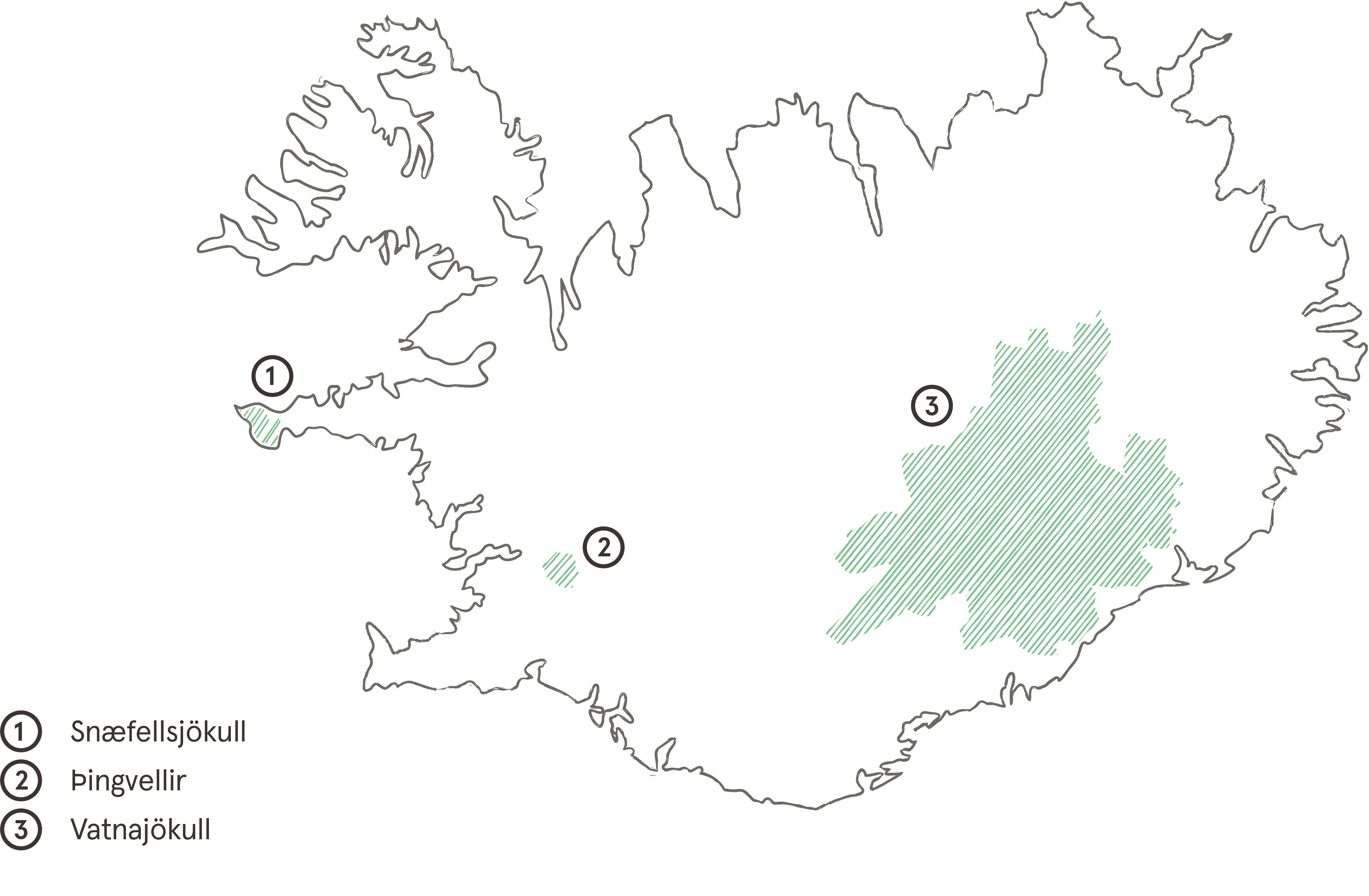

“The public is allowed to travel on the terrain and stay there for legitimate purposes. This right is accompanied by an obligation to take good care of the country’s nature,” states the nature conservation law stressing that people should show full consideration for the landowner and other right holders [...] and follow their guidelines and instructions regarding travel and handling around the country[4]. The nature conservation law also defines the different types of protected areas, including national parks, with the common purpose to preserve the nature of the area, allow the public to get to know and enjoy its nature and history, promote research and education about the area and strengthen economic activities in the vicinity of the national parks. There are 115 protected areas in Iceland, hereof three national parks, of which two are designated UNESCO Heritage Sites.

Þingvellir National Park, a designated UNESCO World Heritage site since 2004, was initially established in 1928 when it became the first protected site in Iceland. Located in the southwestern part of Iceland, about 50 km from the capital, Reykjavík, Þingvellir National Park covers an area of 228 km²[5]. The history of Þingvellir, from the establishment of the Althing around 930, gives an insight into the spatial setting of the democratic forum of the Icelandic republic during the Viking Age, which, together with various natural phenomena, create a unique cultural landscape. From the settlement of Iceland, Þingvellir has been a destination for travellers and the site of national festivals. Originally, Icelanders travelled to Þingvellir to attend large feasts in relation to the annual parliamentary session. Now, it is amongst the most visited sites in Iceland, with service buildings, information centres, and an increasing number of constructed pathways and viewing platforms to enable access to different nature sites while protecting vegetation from the pressure of growing numbers of visitors.

Vatnajökull National Park is the second-largest national park in Europe, covering close to 14% of the total surface area of Iceland, including the Vatnajökull glacier, the largest glacier in Europe. It was established in 2007, merging a few previously protected sites into one. In 2019, Vatnajökull National Park was approved by the UNESCO World Heritage List, based on its unique nature and diverse landscapes created by the interplay of volcanic activity, geothermal energy, and streams with the glacier itself[6].

Snæfellsjökull National Park is located on the outskirts of Snæfellsnes in western Iceland. It is about 170 km² in size and the country’s first national park to reach the ocean.

In addition to the national parks, Reykjanes Geopark at the Reykjanes Peninsula and Katla Geopark in South Iceland have been included on the new UNESCO list of geoparks recognising “the importance of managing outstanding geological sites and landscapes in a holistic manner”[7], in accord with the definition that “a UNESCO Global Geopark uses its geological heritage, in connection with all other aspects of the area’s natural and cultural heritage, to enhance awareness and understanding of key issues facing society, such as using our earth’s resources sustainably, mitigating the effects of climate change and reducing natural disaster-related risks.”[8]

Fragile and life-threatening nature

Due to the sudden and immense growth in visitor numbers in the early 21st century, many natural sites in Iceland became significantly affected. Where the road system and the urban milieu escaped, the Icelandic host faced challenges greeting its guest, no longer a trained hiker, but nevertheless wandering in untouched landscapes, not aware of its danger nor fragility and unfamiliar with the codes of conduct known to the experienced hiker.

Along with nature protection rapid development of infrastructure had to be undertaken in order to accommodate travellers’ primordial needs when off the grid and to promote the security of visitors sometimes threatened by weather and site conditions. Small- and large-scale infrastructures were to be designed and constructed. Ranging from hiking paths, viewing platforms and natural spas to the construction of new hotels in the capital area and the expansion of the Keflavík International Airport. All the while, the previous local store in the village became a souvenir shop, and large shipments of rental cars came ashore to bring travellers out of the city and into nature.

Economic pressure and investment in small-scale infrastructure

In 2015, the tourist industry had become the most important export sector for Iceland, and in 2016, the share of tourism in GDP exceeded the share of fisheries which had previously been on top. The proportional importance of the tourism industry had become far greater than in most OECD countries [9]. Simultaneously, the travel period, previously mainly in the summer months, had been extended with increased winter tourism presenting other types of dangers and infrastructural needs than summer travel.

Facing rapid growth in tourism, Iceland increased its investments in small scale infrastructure. In 2011, The Tourist Site Protection Fund , hosted and serviced by The Icelandic Tourist Board, began its operations. The fund's purpose is “to promote the development, maintenance and protection of tourist sites and tourist routes throughout the country, thereby supporting the development of tourism as an important and sustainable pillar of the Icelandic economy. It also aims to promote a more even distribution of tourists throughout the country and to support regional development”[10].

More than 700 projects received funding from The Tourist Site Protection Fund between 2012 and 2020, amounting to around five and a half billion ISK. Contributions to the fund have increased significantly. In 2012, the fund had 69 million ISK at its disposal, but in 2020, the amount had grown to 700 million ISK. Initially the funded projects were mostly initiated by the state or municipalities but in recent years, projects by smaller parties, individual landowners and associations have increased considerably. Cooperation between private and public stakeholders on a regional level has gained more attention. In 2015, the Icelandic Tourist Board and the Tourism Task Force launched the development of Destination Management Plans (DMPs). Working towards coordination of development and aiming for management of flows in each region while strengthening regional initiatives.

As of now, The Tourist Site Protection Fund operates in three main focus areas. Firstly, nature protection and safety, focusing on projects related to nature conservation and visitor security. This can involve directional paths and platforms that guide visitors with the aim to regenerate and protect nature on the site. Secondly, the development of tourist attractions, favouring projects related to the development, construction and maintenance of built structures. And third, design and planning, such as changes to municipal plans, and design of foreseen development and construction. Projects can receive funding for design and planning and later another grant for construction. Initially, grants from the fund were mainly targeted to popular sites but there is increased emphasis on spreading the load by creating new magnets in less visited regions and to support regional development on the basis of destination plans. However, according to an evaluation report on the The Tourist Site Protection Fund, despite greatly increased budgets, there is still an urgent need for more investment [11].

National plan for the development of infrastructure for the protection of nature and cultural heritage

Since 2018, The Tourist Site Protection Fund has been reserved for projects owned or managed by municipalities and private parties. Projects on sites operated by the state, like national parks and preserved areas, receive funding from a national programme to develop infrastructure for the protection of nature and cultural heritage, a strategic twelve-year plan with a policy for infrastructure development on tourist sites and routes. The programme sets goals for site management and sustainable development, protection of nature and cultural heritage, security, planning and design, and tourist routes. A three-year project plan sets out proposals for concrete projects in parallel with the strategic plan.

The board behind the national programme includes representatives from four ministries and the Association of Icelandic Municipalities. In addition, from 2019 through 2021, there was an active Coordination Group with representatives from public institutions; three national parks, Icelandic Forest Service, The Soil Conservation Service of Iceland, The Cultural Heritage Agency of Iceland, The Iceland Tourist Board, Icelandic Association of Local Authorities and Iceland Design and Architecture (ID&A). The group was assigned to define projects to promote professional knowledge, increase quality in design and coordinate the development of infrastructure to protect natural and cultural-historical monuments in tourist sites. ID&A, whose role is to facilitate and promote design as a vital aspect of the future of Icelandic society, economy and culture, was commissioned to pursue and implement some of the projects on behalf of the Coordination Group. These projects were gathered with other relevant projects, including the Nordic project Design in Nature , under the umbrella of Góðar leiðir , Good Paths. A platform for coordination and collaboration between different operators to facilitate access to toolboxes, guidelines, and instructions to project owners and operators. Among them an update of a coherent signage system, originally from 2011 Vegrún , a manual for construction of nature paths nature paths , and guidelines for planning procedures for tourist sites.

Additionally, the Coordination Group has commissioned educational programmes for nature regeneration and best practices in designing, planning, and constructing infrastructure in nature sites. The group’s formal mandate ran out in 2021 and it remains to define further measures of the initiative.

Beyond the tolerance level

“Nature is the main attraction of the Icelandic tourism industry, and systematic efforts are being made to protect it with stress management and sustainability as a guiding principle,” reads Vegvísir í ferðaþjónustu from 2015[12]. Looking back, it can nevertheless be said that the design and implementation of small-scale infrastructure as protection measures for nature came more as a reaction rather than a carefully thought-out plan. In 2015, somewhat in a state of emergency, Stjórnstöð ferðamála, the Iceland Tourism Management Board, was established as a temporary initiative aiming to get an overview of the situation and coordinate research to prepare for action. Focusing on coordination between different sectors, the management board coordinated research on tolerance limits, concentrating primarily on the number of tourists. The Iceland Tourism Management Board’s focus areas were defined as positive tourist experiences, reliable data, nature conservation, competence and quality, increased profitability, and branding Iceland as a tourist destination.

Measuring tools

Data collection on different sites has been facilitated with instruments that measure the number of visitors. Other official measuring initiatives include The Tourism Balance Sheet , an extensive measuring tool for regularly assessing the impact of tourism on the environment, infrastructure, society, and the economy. Initiated by the Minister of Tourism, Industry and Innovation, the project was managed by the Icelandic Tourist Board and developed by EFLA Engineering together with consultants from Tourism Recreation & Conservation (TRC) from New Zealand and Recreation and Tourism Science (RTS) from the United States. The aim is to create the basis for policymaking and prioritising measures to increase coordination. Sustainability indicators were developed based on the tolerance limits of the environment, society, and the economy[13]. On a range of protected areas under official authority the assessment tool has been applied, facilitating the prioritisation of intervention and investment at a given site. However, the defined parameters for measurement assess only the condition of structures and nature at a particular site. More qualitative and aesthetic assessment tools would be a valuable addition to the balance sheet at hand.

Official quality control system

One of the latest government initiatives in sustainable tourism promotion is Vörður, a holistic approach to destination management based on the French model, Réseau de grand sites de France, which defines the framework for destinations in Iceland that are considered unique nationally or globally. The project is managed by the Ministry of Tourism. The first destinations to start the process are Gullfoss, Geysir, Þingvellir National Park and Jökulsárlón. The ambition of establishing such a quality assessment system was initially set in Vegvísir fyrir ferðaþjónustu (Guidelines for tourism ) in 2015 [12].The plan is that by 2022, more sites, including privately owned tourist sites, can apply for assigned membership in the quality control system. Sites assigned with the label Vörður are seen as models for other destinations, fulfilling quality criteria in terms of management, supervision, organisation, facilities, services, nature conservation, safety and more. The sites must demonstrate a long-term commitment to implementing defined management and planning standards, including design, accessibility, education, security, load management and digital infrastructure.

Design traditions and local craftmanship

Infrastructure of an agricultural society becomes a framework of leisure for the urbanite.

Design tradition and local craftsmanship

Small-scale infrastructure in Icelandic nature reflects the geology of Iceland and ingenious use of local building materials, and a story of a nation shifting rapidly from an agricultural to an urban society in the wake of the 20th century. Abruptly, Icelanders were distanced from living with, in and off the land, growing a seed of longing of that exact nature for repose and experience.

Following the introduction of the first motorised fishing vessel at the beginning of the 20th century and the construction of a sturdy stone pier in Reykjavík, fishing replaced agriculture as the primary industry, keeping its status until the 21st century when the tourist industry took over. Revenues from the fishing industry set the stage for urbanisation throughout the 20th century, together with the birth of the Icelandic urbanite who no longer lived with nature but longed for it. Accordingly, a new perception of nature appears in the artworks and literature of the early 20th century, portraying nature as something beautiful and even sublime, yet distant. The prints of artworks by the “Icelandic masters”, framing the solemnity of nature, ended up on a wall in the living room of a new apartment of sons and daughters of nature who now lived in the city.

Until the 20th century, turf farms were the characteristic habitat of Iceland, nestled in the landscape, leaning from the wind with thick earth walls creating good insulation. The grass roofs grew naturally from the landscape, creating small hills as seen from the exterior perspective. In the early 20th century, concrete became Iceland's local building material. Hence, the texture of the built environment jumped directly from earth to concrete, made of volcanic sand abundant in the estuaries and beaches along the coast.

In parallel with urbanisation in the 20th century, outdoor leisure activities grew steadily with a surge in hiking, mountain skiing, recreational fishing, and bathing. In the 1920s, the first outdoor hut to support leisure activities in nature was built in Lækjarbotnar, close to Þingvellir. Iceland Touring Association (FÍ) was founded in 1927. Today, the association runs 40 mountain huts across Iceland, mainly along the most popular hiking trails.

As part of a swimming education movement in the first decades of the 20th century, local communities in many areas constructed local and outdoor swimming pools, often close to hot water sources that previous generations had bathed in. Weathered and sensitive structures from history, these pools have later attracted travellers and later, at times, excessive intrusion and damage like in the examples of Seljavallalaug and Hrunalaug.

Cairns, conical structures of stacked stones laid decades and even centuries ago, still serve as signposts in Icelandic landscapes where people have wandered since the island’s settlement. Together, the cairns in the open landscape create negative lines indicating old routes for hikers and horse-riders, travelling with goods and running errands in all weather in the agricultural society, usually taking the shortest route over hills and mountains between the distant farms. Apart from guiding the way, the cairns would serve as information infrastructure, as wanderers would sometimes leave notes between the rocks, a poem, a gentle word on how to proceed, what to be aware of, or what to look for. The type of stones used for these conical structures varies from area to area, from old basalt rock in the east and west to younger lava stones in areas on top of the Mid-Atlantic-Ridge, which lies underneath Iceland from the southwest through the northeast – demarking the zones of volcanic activity. This variety of building materials and building techniques is also found in other historic structures like trails, pathways, steps, walls, and fences laid by different stones, with local versions in each part of the country. The differences are explained by specific knowledge passed on through local craftsmanship and the natural material palette depending on the geological formation of each area. Along the old routes, there were huts built to shelter wanderers and farmers herding sheep from the highlands before the first snow. Like all other habitats, these huts were initially built of local material, mixing stone, rock, and earth with wood, which was scarce and therefore used sparsely and thoughtfully. A built lesson in sustainable design and building methods that warrants further study to unleash its potential in relation to future design in nature.

Current designs and future visions

Pristine nature, now with full service.

The twenty-first century has given Icelandic natural landscapes a new purpose as part of a recreational itinerary and experience of the global citizen welcoming the open invitation to seek temporary physical and mental recovery from the hazy urban world. Therefore, tourism has instigated new forms of urbanisation in remote areas and natural landscapes that can be observed through urban interdependencies within Iceland and beyond. As a result, the typical traveller in Iceland is no longer the experienced nature hiker but someone interested in experiencing nature while enjoying and valuing full service. Interestingly, although previously intact landscapes are now boosted with man-made infrastructures like trails, fences, signs, and poles, they still appear pristine and untouched in the eyes of the visitor[16].

Step by step and social cohesion

Tourism has presented new challenges regarding versatility and social cohesion concerning the design and planning of public spaces - where landscapes configure the ultimate space for the public and wildlife. The villages around the coastline have a new role to fulfil as service centres and gateways to the Icelandic wilderness and animal habitats. This role brings about new social and economic potential as well as challenges for municipalities that need to accommodate a growing number of visitors, all while mediating their smooth interaction with nature and wildlife.

When at its best, infrastructure that serves tourism serves the whole society by promoting the well-being and prosperity of the inhabitants. Examples of infrastructure improvements serving both locals and visitors include Borgarfjörður Eystri Visitor Centre. It’s an initiative that grew out of a humble viewing platform in Hafnarhólmi, a summer habitat of puffins, honorary yet temporary inhabitants of Borgarfjörður Eystri, greeted ceremonially upon their arrival in spring. The modest timber platform and stairs have now spun off a 300 m² multifunctional visitor centre that provides a framework for various activities for tourists, fishermen and residents of the village. The visitor centre that was built in concrete came about after the municipality entered into a collaboration with the Architectural Association in formulating goals and emphasis in a competition brief. In fact, design competitions have been increasingly used as a tool to develop popular tourist sites. Examples include Borgarfjörður Eystri and Baugur in the East, Bolafjall in the west and Leiðarhöfði in the south, all projects that are yet to be completed. All these projects have been initiated by small municipalities with the aim to enable access to and enhance experiences in natural environments. A complex and multifaceted endeavour where design competitions are a way for locals, landowners and municipalities of all sizes to engage with professional design communities. Design competition preparations can be facilitated by grants from The Tourist Site Protection Fund. However, they still demand long-term engagement, professional capacity, and funds from the project owner to achieve an ambitious vision, described in a competition brief, through projection.

Since 2018, the majority of projects supported by The Tourist Site Protection Fund have been initiated by locals where the landowner or municipality has coordinated and prepared for planning, design, and construction. In many cases, these are ingenious and well implemented projects while in others further guidance and expertise and even direct involvement of third parties would have been necessary. There is an evident need for applicable tools and access to expertise in design and more aspects of a nature site intervention as well as further financing for construction and maintenance of structures where the project owner can range from an individual, to a large municipality.

Protecting, bathing and weathering

Since ancient times, Icelanders not only swam, they also bathed in geothermal waters from natural sources and created hot tubs to dip in, close to their dwellings. The Guðlaug Baths project derives in part from a rich local ocean-swimming culture in the coastal town Akranes. The baths are nestled in the rocky barrier by the sand beach, which protects the village from the breakwater. As such, the baths form part of a functional protection structure as well as an aesthetical and recreational structure that has made Akranes, a few kilometres off the Ring Road, a worthwhile destination. Another example is Hrunalaug, a historic bathing infrastructure that has shown to be a popular attraction. Located on private property, the owners did not plan for visitors and have faced challenges in protecting the historic infrastructure and its surroundings from harmful intrusion. Hrunalaug is an example of vernacular design, of organic nature, and local materials that need constant mending and maintenance. An overview of the funding allocations shows that many projects receive repeated funding for maintenance and reparations, which raises questions of durability and an eventual need to promote resilient design strategies that take weathering forces better into account.

Durable design for safety and sensation

Since its establishment in 2011, safety has been a top priority for The Tourist Site Protection Fund. Ever since the first rescue squad was formed in Iceland in 1918, following frequent sea accidents and injuries along the shores, Icelandic rescue teams have put themselves on the scales to ensure public safety in Icelandic landscapes. With the increased number of foreign visitors, the volunteers in the Icelandic rescue teams have frequently headed out to help travellers under difficult, even life-threatening circumstances. Safetravel is a privately initiated and publicly-funded accident prevention project run by Landsbjörg, the Icelandic Association for Search and Rescue. The aim is to provide information to travellers and various services to limit risky behaviour, prevent accidents, and promote safe travel around the country.

Brimketill is a water experience project. An iron platform invites visitors to stand in the gushing waves, promoting safety by keeping visitors away from the slippery rocks. Brimketill is one of many examples of structures designed to respond to a demanding environment. Although the metal structure withstands the waves, the natural path toward the platform needs regular repair and maintenance due to the constant onslaught of the ocean waves, again pointing toward the necessity of robust and resilient structures.

Flexibility for landscapes in constant movement

In a context of constantly changing landscapes with sensational national phenomena like volcanoes and geysers that can gush and erupt when and where no one expects, the flexibility of strategies and structures is essential. Constructed stair at Saxhóll crater in Snæfellsnes and the systemic project hovering trails , which have been installed at Hveradalir (Hot Spring Valley), are both elevated from the ground. The aim is to minimise contact with the ground and protect nature from intrusion. While the stairs at Saxhóll crater can be removed without consderable trace, the hovering trails are designed for movability with a modular design that enables easy disassembly and reassembly. The trails can be adapted to the movements in the landscape, and in the event of an earthquake, the structure is designed to withstand pressure, even if some of the individual pillars might break[17].

Contested notion of access

Previously many coastal areas were only accessible by water. Vast areas of Iceland remain intact, and large parts of the inlands are only accessible during the peak of the summer months. A study from 2013 showed that 43% of Europe’s wilderness is in Iceland (xxx). Currently, there are contested views on whether remote areas in the highlands should be made more accessible for cars or, rather, left in the current state in order to protect them and allow for peaceful visits of hikers. According to the management and protection plan of Vatnajökull National Park, certain areas have been closed for car access, favouring the nature experience of hikers and other visitors.

Location-specific measurements of visitor numbers in Vatnajökull National Park show that the increase in visitors is site-specific within the park. Visits in areas close to road access and facilities increased, while the more remote areas remain reserved for the few[17]. This points toward the importance of site-specific approaches, scalability and a careful approach to each site. Some sites and areas would benefit from more built structures, while others might benefit from initiatives designed to reduce the need for infrastructure. And even removal of infrastructures that ease access to the given spot of the given site.

Network of connected points

One of the assessment criteria of The Tourist Site Protection Fund is the location of a site in relation to the local Destination Management Plan. Coordinated destination management with appropriate design for different sites can limit conflicts between different stakeholders, which is one of the focus areas of the Tourism Balance Sheet when measuring the tolerance limits of the local society.

A growing trend is to approach destinations as points in a network forming circuits that demand holistic design strategies for the assembly of different sites and their spatial and narrative interrelationship. A story that becomes the foundation for the marketing of an area with connected sites. The oldest and most visited circuit is the Golden Circle in southern Iceland, covering about 300 kilometres, with the primary sites Geysir, Gullfoss waterfall and Þingvellir National Park. The Golden Circle had close to 2 million visitors in 2019. Other and more recent circuits are the Diamond Circle in North Iceland, with the primary sites of lake Mývatn, Ásbyrgi Canyon, Dettifoss waterfall in Vatnajökull National Park and Goðafoss waterfall.

The project that received the highest grant from The Tourist Site Protection Fund in 2021 was a network project in the vicinity of the Vatnajökull glacier initiated by Hornafjörður Municipality. A walking and cycling path between Svínafell and the national park in Skaftafell is to be designed and constructed in collaboration between local stakeholders. The so-called glacier route will connect the service and residential core of the area to reuse existing path structures, which will be restored and relinked. The project accords with the destination management plan of South Iceland.

Scalability

The accessibility to different sites on the above-mentioned circuits varies. In the case of the Diamond Circle, Goðafoss waterfall is by the central Ring Road, while some of the attractions inside of Vatnajökull National Park are more remote and have hitherto been accessible only during summer. The expected number of visitors all year round promoted in the destination management plan demands on sturdy infrastructure, which has already been put in place in Goðafoss in accord with local inhabitants. On the other hand, large-scale interventions into the landscapes of Vatnajökull National Park have been contested. The implementation of destination management plans and the launch of marketing campaigns for whole areas must be linked to a more refined design strategy for edge destinations on the circuits that warrant further work. Protection measures for lesser-known hidden gems in the vicinity of the main circuits must be in place before promoting them to a larger audience.

More cross-collaboration is needed Although there are signs of increased coordination between different agents involved in tourism, future scenarios are often drawn up solely by representatives of a defined tourism industry without involvement of members of the design or art community, nature protection, scholars, and the like. Furthermore, apart from the coordination group for the National Plan for Infrastructure, active between 2019 and 2021, officially established steering groups are often involved in isolated issues. One with a focus on tourism, another on planning and protection of natural and cultural heritage, and a third focused on design. And so forth. Thus, policy and planning work in the realm of tourism in Iceland circulates in an established tourist industry where increased numbers seem to be the principal success criteria, which goes hand in hand with plans put in force in order to limit negative impact on society and environment. In accordance with the Icelandic government’s focus on increasing foreign visitor arrivals, there have been diverse branding initiatives from the official promotional office of Iceland. Many of these initiatives have aimed to extend the travel period around the country, with campaigns instigating winter tourism and distributing visits around the country. However, more coordination is required between those who invite the visitors and those who host and greet the visitors; a plethora of private and public agents that partake in creating links on a chain of infrastructure, facilities and sites that need to be prepared for the influx of visitors all year round. Further, all sustainable tourism should preferably be aimed at and designed for the domestic traveller and the local as well as the foreign visitor, encouraging everyone‘s responsible and enriching engagement with nature, promoting health and quality of life for all.

Collaborating by means of design

Although site-specific conditions demand site-specific solutions, Iceland has been facing challenges that are well-known categorically and have already been dealt with elsewhere. Sharing experience through Nordic collaboration is highly valuable in this respect. A Nordic network could advance the development of a Nordic set of design principles that would form a basis for a Nordic Policy of Design as a tool to promote valuable nature experiences without harmful nature intrusion. However, it is through physical interventions, designed, built and maintained, that we eventually learn. In a quest for sustainable performance of built structures, innovative attitude and state-of the-art knowledge of design should be promoted. Nordic collaboration that facilitates room for experimentation and research on a range of aspects like how design can augment experience of nature by inviting the engagement of the senses, or how design strategies can further robustness against weathering forces, would be valuable.

To increase efficiency and resilience, it is essential to work comprehensively and collectively with more cross-sector, cross-country and cross-border collaboration where design is not end-of-pipe. The potential of design in the context of sustainable tourism lies in part in strategic design. Inherent holistic thinking and aesthetic considerations, the agility and potential of design to create links between lessons from the past and the needs of the future. The applicability of design processes to work with scenarios of movement and human interaction with its surroundings are all methods that can be applied more systematically when it comes to decision-making to prepare for interventions in natural environments. Further, acknowledging that every species has an equal right to thrive on earth, artists, designers, and scholars are paving the way with an empathic and personal approach. Instigating a change from a human-centred to a nature-centred approach. Sustaining sensitive ecosystems by prioritising their protection and regeneration. An essential part of this ideological change, to be followed through in action, is to allow for people’s engagement with and connection to nature. Therefore, design and design strategies that promote and provide tools for responsible engagement with nature is invaluable.

Notes 1 Halldór Björnsson, Bjarni D. Sigurðsson, Brynhildur Davíðsdóttir, Jón Ólafsson, Ólafur S. Ástþórsson, Snjólaug Ólafsdóttir, Trausti Baldursson, Trausti Jónsson. 2018. Loftslagsbreytingar og áhrif þeirra á Íslandi – Skýrsla vísindanefndar um loftslagsbreytingar 2018. Veðurstofa Íslands. https://www.vedur.is/media/loftslag/Skyrsla-loftslagsbreytingar-2018-Vefur-NY.pdf 2 Gunnar Þór Jóhannesson & Katrín Anna Lund. Áfangastaðir í stuttu máli . Háskólaútgáfan & félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands, Reykjavík 2021. 3 Hagstofa Íslands. (2003–2018) Farþegar um Keflavíkurflugvöll eftir ríkisfangi og árum 2003–201 8. https://px.hagstofa.is/pxis/pxweb/is/Atvinnuvegir/Atvinnuvegir__ferdathjonusta__farthegar/SAM0206. px" \h 4 Lög um náttúruvernd nr. 60/2013. https://www.althingi.is/lagas/nuna/2013060.html 5 Þjóðgarðurinn á Þingvöllum stefnumörkun 2018-2034. https://www.thingvellir.is > um þjóðgarðinn > stefnumörkun Þingvallanefndar > https://www.thingvellir.is/media/1754/a1072-023-u02-stefnumorkun-vefur.pdf 6 Snorri Baldursson. Vatnajökulsþjóðgarður, gersemi á heimsvísu. JPV útgáfa 2021. 7 Unesco. https://en.unesco.org/global-geoparks 8 Ibid. 9 Íris Hrund Halldórsdóttir. Ferðaþjónusta á Íslandi og Covid 19. Staða og greining fyrirliggjandi gagna. Ferðamálastofa. 2021. https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/static/files/ferdamalastofa/Frettamyndir/2021/juli/seigla-i-ferdathjonustu-afangaskyrsla-rmf-juli-2021-m-forsidu.pdf 10 Lög um Framkvæmdasjóð ferðamannastaða 75/2011. https://www.althingi.is/lagas/nuna/2011075.html 11 Atvinnuvega- og nýsköpunarráðuneytið. Skýrsla ferðamála-, iðnaðar og nýsköpunarráðherra um stöðu og þróun Framkvæmdasjóðs ferðamannastaða. Atvinnuvega- og nýsköpunarráðuneytið 2021. https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/static/files/ferdamalastofa/Frettamyndir/2021/januar/210111-atvinnuvegaraduneytid-framkvaemdasjodur-ferdamanna-v6.pdf 12 Atvinnu- og nýsköpunarráðuneytið. Vegvísir í ferðaþjónustu. https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/static/files/ferdamalastofa/tolur_utgafur/Skyrslur/vegvisir_2015.pdf 13 Stjórnarráð Íslands. https://www.stjornarradid.is/default.aspx?pageid=0e00328a-0ec4-492b-97f6-f32d41b2fd25#Tab0 14 Snorri Baldursson. Vatnajökulsþjóðgarður, gersemi á heimsvísu. JPV útgáfa 2021. 15 Anna María Bogadóttir. “Water as Public Greenspace: A Remotely Urban Perspective on Iceland” in Green Visions: Greenspace Planning and Design in Nordic Cities, Arvinius + Orfeus Publishing, Stockholm 2021. 16 Gunnar Þór Jóhannesson & Katrín Anna Lund. Áfangastaðir í stuttu máli . Háskólaútgáfan & félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands, Reykjavík 2021. 17 Hovering trails. https://www.hoveringtrails.com 18 Snorri Baldursson. Vatnajökulsþjóðgarður, gersemi á heimsvísu. JPV útgáfa 2021. 19 Norðurstrandaleið. https://www.arcticcoastway.is/en/about/about

Bibliography, anna maría bogadóttir. “water as public greenspace: a remotely urban perspective on iceland” in green visions: greenspace planning and design in nordic cities, arvinius + orfeus publishing, stockholm 2021. anna dóra sæþórsdóttir et al. þolmörk ferðamennsku í þjóðgarðinum í skaftafelli. ferðamálaráð íslands, háskóli íslands, háskólinn á akureyri, 2001. downloaded from: https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/static/files/upload/files/skaftafell.pdf . gunnar þór jóhannesson & katrín anna lund. áfangastaðir í stuttu máli . háskólaútgáfan & félagsvísindasvið háskóla íslands, reykjavík 2021. halldór björnsson, bjarni d. sigurðsson, brynhildur davíðsdóttir, jón ólafsson, ólafur s. ástþórssson, snjólaug ólafsdóttir, trausti baldursson, trausti jónsson. 2018. loftslagsbreytingar og áhrif þeirra á íslandi – skýrsla vísindanefndar um loftslagsbreytingar 2018. veðurstofa íslands. downloaded from: https://www.vedur.is/media/loftslag/skyrsla-loftslagsbreytingar-2018-vefur-ny.pdf íris hrund halldórsdóttir. ferðaþjónusta á íslandi og covid 19. staða og greining fyrirliggjandi gagna. ferðamálastofa 2021. íslensk ferðaþjónusta samstarfsverkefni kpmg, ferðamálastofu og stjórnstöðvar ferðamála — október 2020 sviðsmyndir um starfsumhverfi ferðaþjónustunnar á komandi misserum stjórnstöð ferðamála. downloaded from: https://home.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/is/pdf/2020/10/svidsmyndir-um-framtid-ferdathjonustunnar-10-2020.pdf landsbankinn. hlutur ferðaþjónustu í landsframleiðslu í fyrsta sinn meiri en sjávarútvegs [the share of tourism in gdp for the first time greater than fishing industry]. hagsjá - þjóðhagsreikningar. landsbankinn 2018. lög um framkvæmdasjóð ferðamannastaða 75/2011. lög um náttúruvernd nr. 60/2013 snorri baldursson. vatnajökulsþjóðgarður, gersemi á heimsvísu. jpv útgáfa 2021. vegvísir í ferðaþjónustu. atvinnuvega- og nýsköpunarráðuneytið og samtök ferðaþjónustunnar 2015. downloaded from: https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/static/research/files/vegvisir_2015-pdf, author information.

Anna María Bogadóttir, [email protected]

Related case studies

Gunnuhver viewing platforms, fjaðrárgljúfur viewing platform, saxhóll stairway, hrunalaug baths, grábrók pathway, brimketill viewpoint.

Expert overviews from the Nordic countries that together give insights into tradition, trends and future visions for design in nature in the Nordic region.

The national overviews identify the potential of design in nature from a wide angle and indicate how particular solutions come about strategically in light of site-specific challenges — portraying the formal and informal framework of protection, collaboration, and financial and planning structures.

Each national overview is presented in three chapters: i / characteristics of nature and tourism ii / design traditions and local craftsmanship iii / current trends and future visions

Tourism in Iceland

Jump to a section.

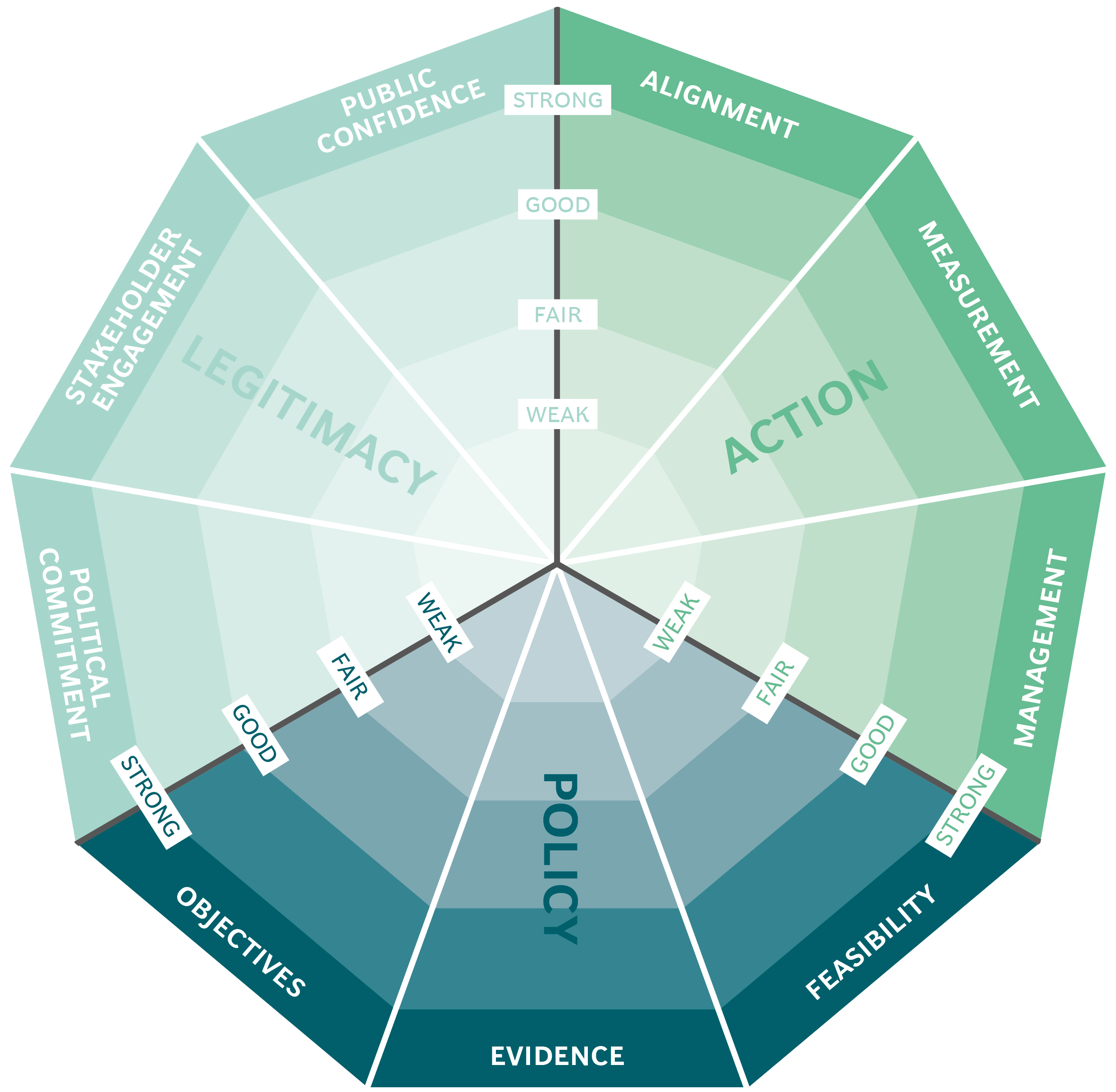

The initiative

The challenge

The public impact

- Stakeholder engagement Good

- Political commitment Good

- Clarity of objectives Strong

- Strength of evidence Strong

- Feasibility Strong

- Management Strong

- Measurement Good

- Alignment Strong

Bibliography

In May 2012, PKF International was commissioned by Promote Iceland to carry out a master mapping project for the Icelandic tourism industry and to establish its foreign direct investment potential. It had the following objectives:

- To increase the profitability of the tourism industry.

- To engage in systematic development of tourist destinations, effective product development, and promotion and advertising work so as to create the opportunity to lengthen the tourist season, reduce seasonal fluctuations, and encourage tourists to travel throughout the country.

- To enhance the quality, professionalism, safety, and environment awareness of the tourism sector.

- To define and maintain Iceland's uniqueness as a tourist destination, in part through effective analysis and research.

- To create a platform for the government and tourism industry stakeholders to formulate a long-term strategy.

A new Tourist Control Centre has been established to coordinate operation and work out ways in extensive cooperation all over the country for an industry that is very complex, and which is under the administration of four ministers.

In order to study the tourism industry, several steps were undertaken, including:

- Conducting a limited international tour operator survey to build on existing travel surveys

- Evaluating the key geographic source markets and segments and identifying potential opportunities.

- Formulating a ten-year vision with clear targets.

- Specifying the institutional framework and tourism policy requirements.

- Preparing an annual monitoring and evaluating the grid to enable the Icelandic tourism industry to monitor the progress of the implementation of the long-term strategy.

- Preparing an indicative annual budget.

Stakeholder engagement

Political commitment

The Icelandic government is generally supportive of tourism in Iceland:

- It set up the Tourist Site Protection Fund, which supports the development and maintenance of infrastructure that protects nature at frequently visited attractions and at new sites. [2]

- The Icelandic Tourist Board works in close co-operation with governmental agencies, municipalities and legislators.

Clarity of objectives

Strength of evidence

To understand the requirements of the tourism industry, surveys and SWOT analysis was undertaken. The Tourism Strategy Group was replaced with the Tourism Council, to implement the policy, as recommended by the OECD.

In 2012, PKF team conducted surveys with 22 visitors, who were from from the UK, USA, Canada, Denmark, Italy, Netherlands, Germany, Spain, Austria, Japan and Switzerland. The purpose of the survey was to understand the visitor experiences and perceptions at first hand, rather than to undertake a comprehensive analysis. It was found that Iceland is more expensive than its Nordic competitors, mainly due to the high cost of flights and car hire.

Feasibility

To expand the tourism industry in Iceland, many approaches were undertaken to test the feasibility of the policy. Surveys were conducted, funding mechanisms were reviewed, and environment and social carrying capacity were taken into consideration.

A development fund for tourism, national parks and protected areas is to be established with the revenue levied from tourist taxes. Funding mechanisms were also reviewed to close the funding gap for infrastructure at tourist sites. Environmental and capacity concerns were taken into consideration, to establish which tourist destinations in each region required better access and traffic management.

On the basis of an agreement made between the Icelandic government, the Icelandic Association of Local Authorities, and the Icelandic Travel Industry Association (SAF), the Tourism Task Force was set up, which will continue in operation until the end of 2020.

The Tourism Task Force consists of four cabinet ministers, four representatives of the tourism industry, and two municipal representatives. The Task Force follows the Road Map for Tourism and its managing director draws talent from Iceland and abroad to address the most pressing priorities in the tourism industry.

It will ensure that the next five years are used to lay the solid foundations that are needed by the Icelandic tourism industry. The Task Force's function is to coordinate measures and find solutions in collaboration with government and municipalities, as well as the support the framework for growing tourism throughout the country.

Measurement

Performance measurement is based on the goals achieved in a particular year. These statistics are maintained and published by the Icelandic Tourist Board.

It is evident, however, that Promote Iceland and the Tourist Board need to adopt a robust approach to monitoring and evaluating the performance of the tourism industry on a regular basis, in close co-operation with Statistics Iceland and the Tourism Research Centre.

There is extensive cooperation between stakeholders and the government, as in the formation of the Tourism Task Force.

There is a steering group within the Task Force of public, private and other stakeholders which meets monthly and is chaired by the minister for industry and commerce. It also includes representatives from:

- Other Icelandic ministries that are relevant to tourism (finance, the environment, and the foreign office)

- Private firms (represented by industry associations, etc)

- Other tourism organisations (e.g., travel agents)

The steering group tracks progress, resolves issues, allocates roles to sector entities and takes decisions, as appropriate. The group's staff are responsible for such tasks as managing coordination between sector stakeholders and providing operational support for nature funds. There has, overall, been extensive cooperation between municipalities, travel agents and other authorities in formulating policy.

Tourism in Iceland in Figures, April 2014, Icelandic Tourist Board

Environmental Performance Reviews, Highlights 2014 , OECD

Iceland 2020 - governmental policy statement for the economy and community Knowledge, sustainability, welfare

The Public Impact Fundamentals - A framework for successful policy

This case study has been assessed using the Public Impact Fundamentals, a simple framework and practical tool to help you assess your public policies and ensure the three fundamentals - Legitimacy, Policy and Action are embedded in them.

Learn more about the Fundamentals and how you can use them to access your own policies and initiatives.

You may also be interested in...

ChileAtiende – a multi-channel one-stop shop for public services

Bansefi: promoting financial inclusion throughout mexico, formalising the appointment and compensation of chile’s senior civil servants, rainfall insurance in india, microcredit in the philippines, german institute of development evaluation (deval), how can we help.

National Geographic content straight to your inbox—sign up for our popular newsletters here

Over seven million people visit "La Joconde," or the Mona Lisa, by Leonardo Da Vinci at the Louvre Museum in Paris each year.

Overtourism: too much of a good thing

The global tourism boom isn’t slowing down. What can travelers do to keep things in balance and aid in sustainability?

Reykjavík isn’t what it used to be. The Icelandic capital’s main shopping street, Laugavegur, now belongs to tourism. Shops bill themselves in English, not Icelandic: Icemart, Chuck Norris Grill, a “Woolcano” gift shop. A lone hardware store has survived the wave of touristification.

The term “ overtourism ”—too many tourists—has been moving from travel-industry jargon into the mainstream, propelled by such flash points as Venice , Amsterdam , and Barcelona , where exasperated locals unfurled “TOURIST GO HOME” banners in 2017.

The phenomenon is global and has even reached chilly, expensive Iceland—a relative newcomer to travelers’ bucket lists. Travel media have affixed the overtourism label not just to Reykjavík but to the whole country. So when I arrive after eight years away, I am apprehensive. How bad will it be? And how can travelers be part of the solution, not part of the problem? [Find amazing alternatives to destinations experiencing overtourism.]

I first explored Iceland as a recent college grad in 1973, entranced by vast scenery, the modern culture with its Old Norse language, and the in-your-face volcanic geology. I kept coming back, making my previous visit in 2010, right before the tourism boom. By 2017, Iceland was drawing over two million visitors annually—six times its national population.

The Blue Lagoon may be one of Iceland’s most popular attractions, but author Jonathan Tourtellot says it’s actually the one place in Iceland he’s not worried about. “It’s entirely artificial, well managed, handy to the airport, and expensive,” he says.

When does such a fast-rising tide become an unacceptable tsunami? For Icelanders who are not making money from tourism—and even for those who are—overtourism means disruption to their lives and their city. “The Reykjavík center is all hotels and Airbnbs now,” says my friend Ingibjörg Eliasdóttir. “Downtown is out of hand. Real estate prices have gone up so high that students can’t afford to live here anymore.”

The tourism flood would have arrived sooner or later. The number of international trips taken each year worldwide has gone from some 25 million in the 1950s, right before the commercial jet age began, to 1.3 billion in 2017. International arrivals are projected to reach a possible three billion by 2050. Yet the sights and places all these people visit remain the same size.

Causes of the tourism surge reportedly range from easier border crossings and cheap regional carriers to subsidized airline fuel and Airbnb, which increases a destination’s accommodations capacity. Look deeper, though, and you find three powerful trends. First, Earth’s population has nearly tripled since the 1950s, when mass tourism was just getting started. Second, affluence is growing even faster, with the world’s middle class expected to reach 4.2 billion by 2022. Third, technological changes from GPS and social media to wide-body jets and towering cruise ships carrying town-size populations have revolutionized travel.

I once complained to the CEO of a major cruise line about how each ship disgorges thousands of passengers into the confined medieval streets of Dubrovnik , Croatia . “Don’t people have a right to visit Dubrovnik?” he countered. Perhaps, but when people keep arriving in groups of 3,000, it profoundly changes a place.

Airlines can boost heavy traffic as well. Icelandair’s free-stopover offers put hundreds of tourists daily on the accessible Golden Circle route, which takes in the historic site of Thingvellir, the Gullfoss waterfall, and geothermal Geysir. The first two are large enough to handle several hundred visitors, but compact Geysir shows signs of overtourism—trash, overcrowding, and a tourist-trap sprawl mall right across the road.

- Nat Geo Expeditions

This fast-growing mass travel poses real threats to natural and cultural treasures. Wear and tear on fragile sites is one issue. So is cultural disruption for local people. And visitors receive a degraded experience. [Discover 6 ways to be a more sustainable traveler.]

Pressure for change comes less from tourists than from locals and preservationists. Officials in Barcelona, one of the world’s busiest cruise ports, have promised tighter controls on mass tourism, short-term apartment rentals, hotel development, and other challenges. Dubrovnik has plans to restrict the number of ships that can dock. Italy ’s Cinque Terre has put limits on hikers. Amsterdam is focusing on tourist redistribution techniques. In Asia , where tourism growth is rampant, governments have closed entire islands to allow recovery, such as on overbuilt Boracay in the Philippines and overtrodden Koh Tachai in Thailand . As for Iceland, the government has launched a Tourist Site Protection Fund, and Reykjavík has banned permits for new hotel construction downtown.

The low sun casts long shadows, revealing the magnitude of the crowd size around the Strokkur Geyser in Iceland.

Destination stakeholders are not the only ones who can take action. What can a smart traveler do?

Adopt a wise-travel mindset.

When you arrive in a place, you become part of that place. Where you go, what you do, how you spend, whom you talk to: It all makes a difference. Try to get out of the tourist bubble and see how locals live. Treat every purchase as a vote. In Iceland, María Reynisdóttir of the national tourism bureau suggests looking for the official quality label Vakinn when buying souvenirs or booking lodgings.

Avoid peak times.

Hit museums and sights early, before crowds arrive. Avoid peak seasons as well. [Visit the world's best museums.]

Stay in homes.

Booking an Airbnb listing with a friendly host can add depth to your stay, but avoid hosts who peddle multiple units bought just for short-term rentals. That practice can boost property values beyond what locals can afford.

Tell tourism authorities what you think. They worry about reputation. Post online reviews about whether you think the destination is doing a good job of managing tourism.

Earth is a big place, and much of it is still undervisited. In Iceland this past August, my wife and I headed north to see where a sign-posted route called the Arctic Coast Way will open in June 2019. Here, far from Reykjavík and well beyond the tour buses relentlessly plying Route 1, we drive past fjords touched by fingers of fog and mountainsides laced with waterfalls.

Just short of the Arctic Circle we stop at the Guest-house Gimbur, empty except for us. “Mid-August is the end of the season,” explains our hostess, Sjöfn Guðmundsdóttir. Relaxing in her hot tub, watching a lingering sunset at the southernmost reaches of the Arctic Ocean, I reflect on something else she said: “Slow tourism is my motto.” It can be yours too.

Related Topics

- SUSTAINABLE TOURISM

- HIGHWAYS AND ROADS

You May Also Like

10 of the best UK destinations for spring travel

10 of the best hotels in Vienna, from film-star boltholes to baroque beauties

Become a subscriber and support our award-winning editorial features, videos, photography, and much more..

For as little as $2/mo.

25 essential drives for a U.S. road trip

10 whimsical ways to experience Scotland

The essential guide to visiting Scotland

They inspire us and teach us about the world: Meet our 2024 Travelers of the Year

How to explore Grenada, from rum distilleries to rainforests

- Best of the World

- Interactive Graphic

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- Out of Eden Walk

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- In the Spotlight

- Strategy Toolbox

- Trends & Insights

- The Place2Place Podcast

- The ultimate guide to place brand rankings

- Research and Reports Library

- City Nation Place UK

- WEBINAR: Charting a course to destination stewardship

- City Nation Place Global

- City Nation Place Australasia

- City Nation Place Americas

- The Place Brand Portfolio

Exploring tourism taxation as a method to fund a regenerative future

By Melissa Baird, Communication and Brand Consultant, The GDS-Movement

When COVID-19 turned the world of tourism upside-down, tax relief or cancellation was introduced with the intention of assisting the industry. As the discussions began on how to ‘build back better,’ a key question remains on how a regenerative future can be funded. Could well-designed tourism taxes be part of the answer?

This is the starting point of a newly published White Paper, Tourism Taxes by Design , which explores how tourism taxation can be designed to support recovery and the long-term development of a more resilient and regenerative tourism economy.

The white paper explores the different kinds of tourism-related taxes, the existing models and revenue flows already in place and their impact, including further research into the current funding situation of destination organisations (DMOs) in Europe. Twenty-one out of thirty European countries have implemented tax, levies and duties on travel and tourism services that offer multiple examples and models where tourism tax revenue is used to invest in sustainable tourism development.

As we prepare for recovery, what can we learn from those destinations who are leveraging tourism taxes as a model to create a more sustainable , resilient future?

What role can tourism taxes play in supporting a destination?

Whilst researching for the white paper, we grouped the tourism tax models used under one of seven different headings, sorted from the most commonly seen models through to the gold star standards of regenerative tourism taxation:

Exploring the different taxation designs and models, it is clear that there is no one size fits all solution, although most of the tourism-related taxes have an element of regulatory design. While tourism taxation has generally been perceived as the ‘elephant in the room,’ the white paper research shows that the perceived negative impacts on demand and competitiveness are rather marginal. Furthermore, consumers are inclined to be more willing to pay taxes if there is transparent reinvestment of the tax revenue for ear-marked “good purposes” (sustainability, local community, cultural and natural preservation).

Best practice examples of tourism tax models from around the world

Barcelona: addressing the cost of tourism.

Barcelona is a world leader in tourism policy design and regulation. Since 2012, the city has received €72.7M in tax revenues which have been used on destination management , promotion and development. The city government seems conscious that tourism is not just a benefit, but also in some respects a burden for the destination.

Since the creation of the tax, tourist activity in Barcelona has continued its steady growth curve from 7,1 million guests in the hotels in 2013 to 9,5 million in 2019 according to Statista. Early estimates of Barcelona study indicate that tourism tax revenue covers between 13% and 29% of tourism related expenditure.

Austin, Texas: Funding development and resilience

In 2019 in Austin, Texas, the City Council approved a “live music fund” from the city’s hotel occupancy tax. Fifteen percent of the occupancy tax revenue will be directed to the local commercial music community, while another 15% is to be directed to historic preservation. The remaining 70% is to be directed to the Austin Convention Center.

New Zealand: Tourism taxes to ensure sustainable tourism growth:

On the website, it is clearly stated that tourism tax serves the purpose of making “sure” that New Zealanders' lives are enriched by sustainable tourism growth. It will do this by “investing in projects that will substantively change the tourism system, helping to create productive, sustainable and inclusive tourism growth that protects and supports our environment.” The funds are guided by an advisory group that meets three times a year with expertise and experience across the industry, in tourism investment, in conservation, and in environmental matters.

Slovenia: For industry and destination resilience

In January 2019, Slovenia added an additional “promotion tax” to the existing tourist tax. The amount of the promotion tax is 25% of the tourist tax and is intended for planning and implementation of marketing and promotion of Slovenia. The revenue of the tax goes to the Slovenian Tourist Board.

Levering tourism taxes for place regeneration

Though not as prevalent there are quite a few examples of tourism tax models designed to fund destination development or for broader environmental and community purposes. This taxation’s purpose is regenerative because it is a mechanism to ensure that destinations can generate shared value from tourism and give back to the local communities.

According to OECD, there has been significant increase in the number of taxes with an environmental focus, designed to encourage environmentally positive behaviour change from operators and tourists, or to provide funding to better manage the environmental or otherwise negative impacts of tourism activities.

In regenerative tax models, revenue can be used for infrastructure, community projects, restoration or investment in local culture, nature preservation, education or social projects.

Iceland: Taxes for protection of nature

In recent years, there has been political debate in Iceland over introduction of new taxes to curb the exponential growth in visitor numbers to the country.

Seven design criteria for tourism tax

What, then, are the most essential criteria to consider when creating a tourism tax model for your destination?

1. Earmark and ring-fence: Whether for general tourism promotion or for regenerative purposes, there is a consensus among leading associations, intergovernmental organisations and amongst local stakeholders that tourism tax is a specialised tax and its revenues should be allocated and invested as such.

2. Local governance adds collaborative capability : Local governance and representation is often key to balancing stakeholder interests and to earn political support for the tax regime and support of the local DMO. Local and democratic governance and distribution of funds adds to the legitimacy of the tax and collaborative capability of the destination.

3. High visibility and transparency works with consumers : Case studies prove that tourism taxes are often well received with consumers if communicated as a modest contribution to be used for purposeful, regenerative projects and activities.

4. Public engagement and consultation are key : Governments or destinations looking to introduce or change tourism taxation policies need to engage in open and public conversation.

5. Specify how to comply : In their comprehensive 2017 study, PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) highlights the importance of ensuring compliance with the tax regime. This can be done by offering advice and extensive instructions to less resourceful SMEs and by committing industry associations and platforms. In some member states, tax authorities have committed the large shared platform providers (such as Airbnb and HomeAway) to facilitate the automated collection of occupancy taxes.

6. Monitor and evaluate impact : There is a lack of good data as well as monitoring, evaluation, and analysis of the impact of tourism-related taxes and incentives to ensure they are meeting their stated objectives without adversely affecting tourism competitiveness.

7. Consider both benefits and burdens : For many good reasons, much literature, research, and political advocacy have long focused on the economic and social benefits of tourism in a global world. However, it is vital to also understand and address the “invisible burdens” of the visitor economy to the destination that present themselves in many forms.

Both the research and case studies prove that well-designed tourism taxes can be both practical and meaningful tools in the sustainable management of the destination’s resources. Ultimately, regenerative tax can offer a vital lifeline to recovery.

The research was developed by Group NAO and the Global Destination Sustainability Movement and has been launched in partnership with European Tourism Association (ETOA) with support from nine urban tourism destinations. Read the full white paper here: TOURISM TAXES BY DESIGN

Group NAO works with transformative agendas, ideas and strategies in travel, tourism, culture, and urban development. We are strategic creatives, change communicators and imaginative analysts.

The GDS-Movement ’s mission is to enable destination management professionals to catalyse and co-create sustainable and circular strategies, that will enable destinations of the future to thrive, and society and nature to regenerate.

Watch the webinar launch HERE .

Related reading:

The roadmap for sustainable recovery

Five ideas everyone should take away from the City Nation Place World Congress

Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland is calling

Six tips to be more cost-effective as a place brand and marketing organisation

14 steps to nation branding: a practical guide

Three key concepts as we rethink, retool, and reinvent

COVID-19 - the sequel: communication implications for destination marketing

Discover CNP Connect

Sign up for this fortnightly newsletter to get the latest insights and inspiration straight to your inbox.

By submitting my information, I agree to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Service .

The Place Brand Portfolio is City Nation Place's searchable portfolio of Awards case studies from the past five years.

Related content

Your Local Love

Maximising your ad budget: 10 tips for place brands

How to develop indigenous tourism that empowers, not exploits

Tourism for all: Six community engagement approaches to support your visitor economy

What Is The Elevation Effect?

Beyond sight: How to appeal to all five senses in place branding

All residents should benefit from sharing their places with visitors. But do DMOs know how?

Confirm cancellation.

An error occurred trying to play the stream. Please reload the page and try again.

You can unsubscribe from these emails at any time. For more information on how we process and secure your data, view our privacy policy

By submitting your details you consent to us processing the personal data you have provided in accordance with our privacy policy and terms and conditions

- Attractions & Activities

- Museums & Exhibitions

- Something for everyone

- Restaurants

- Accommodation

- Getting around Reykjavík

- Traveling to Reykjavik

- Trip ideas & Itineraries

- Convenient traveling

- Practical Information

- Hafnarfjörður

- Mosfellsbær

- Seltjarnarnes

- Reykjavik History

- About Visit Reykjavík

- Media center

Krýsuvík Geothermal Area

The wooden walkway, which is the only safe approach to the bubbling and hissing geothermal area, is being replaced, so the area will be closed entirely during construction. The steaming volcanic vents and boiling hot springs alone call for hiking trails to be constantly repaired as there is a lot of wear and tear. During construction, a gravel top dressing will be added to pathways as conditions allow. The project is being carried out with a grant from the Tourist Site Protection Fund for the continued development of the area, which is considered urgent due to safety and nature conservation considerations. All visitors are thanked for their patience during the construction and are referred to numerous other interesting places in Hafnarfjörður at www.visithafnarfjordur.is or destinations in Reykjanes at www.visitreykjanes.is .

Not too far from the centre of Hafnarfjörður rest the remarkable solfatara fields of Krýsuvík, where you’ll discover an expanse of steaming volcanic vents and boiling hot springs, framed dramatically by a range of multi-coloured hills.

A well-maintained boardwalk winds through the bubbling and hissing Seltún geothermal area, with informative signage explaining all the important geological facts. The massive solfatara steaming away on the hilltop is a tempting attraction, even for those with tired legs, and the spectacular view of the surrounding area is well worth the extra legwork. As a short side-trip, you can also explore the coastline, where you’ll discover the stunning cliffs of Krýsuvíkurbjarg—an area renowned for its rich birdlife.

You'll find wildly colourful crater lakes beside the mud pools and sulphur deposits. The Grænavatn, Gestsstaðavatn, and Augun lakes are old explosion craters formed by volcanic eruptions. Grænavatn Lake, 46 meters (150 feet) at its deepest, glows with a deep green hue and is coloured so because of the presence of thermal algae and crystals that absorb the sun's rays. Gestsstaðavatn Lake draws its name from Gestsstaðir, a nearby farm, abandoned during the Middle Ages. On either side of the main road are two small adjacent lakes, called Augun (the eyes).

Just a few minutes' drive from the surreal landscape of the geothermal area sits the stunning Krýsuvíkurberg Cliffs. Here, thousands of seabirds nest in the rugged hillside beside the crashing surf of the Atlantic Ocean. For a peaceful outing, hike along the trail to the edge of the cliffs where it's possible to spot kittiwakes, guillemots, razorbills, and other birds as they dive into the sea to feed or frolic with their flock.

Contact the Hafnarfjörður Tourist Information Centre for a detailed map of the Krýsuvík area, including hiking and walking routes and information on local history, geology, folklore and attractions.

Hafnarfjörður has located about 18 km from the city centre of Reykjavík.

#visitreykjavik

Switch language:

Overtourism is harming the climate. What can be done about it?

New initiatives aim to draw people out of the world’s most popular destinations to lessen tourists’ impact on the Earth.

- Share on Linkedin

- Share on Facebook

Venice has many nicknames: the ‘Queen of the Adriatic’, the ‘Floating City’ and ‘La Serenissima’ – the most serene. But as anyone who has been to Venice knows, on a typical day it can feel anything but serene. The city is notoriously mobbed with tourists. Up to 120,000 people visit Venice each day in peak season, but it has only 55,000 permanent residents. It is a phenomenon known as “overtourism”, where too many people visit the same place at the same time.

Overtourism is a big problem, with 80% of the world’s tourists only going to 10% of the world’s destinations, according to the start-up consultancy Murmuration. Venice is probably the most notorious example, but other European cities such as Barcelona, Amsterdam, Dubrovnik and Prague are also badly affected. The problem does not just make life unpleasant for residents and visits less enjoyable for tourists, it also puts significant strain on the environment and is hurting the climate. So many people flying into the same place degrades local ecosystems and natural defences against the effects of climate change. This in turn is causing worries that these oversaturated cities are going to be particularly vulnerable to climate change.

Go deeper with GlobalData

Q1 2016 Global FPSO Industry Outlook – Decline in Capital Expenditu...

Q3 2016 global fpso industry outlook – persistent delays in planned..., data insights.

The gold standard of business intelligence.

Find out more

Related Company Profiles

Booking holdings inc.

The UN’s World Tourism Organization and the International Transport Forum concluded in 2019 that 5% of global emissions – and 22% of global transport emissions – are from transport-related international and domestic tourism. Overtourism’s worst offender is cruise ship tourism, which in 2016 emitted 24–30 million tonnes (t) of CO₂, with per passenger emissions ranging from 1.2–9t of CO₂ per trip. By comparison, a transatlantic flight emits a bit less than one tonne of CO2 per passenger, according to the International Council on Clean Transportation. That means taking a cruise emits up to nine times more carbon than flying across the Atlantic.

Luring with the lagoon