- Social Studies

- Language Arts

Grade 5 | Grade 6 | Grade 8

Interior Plains Physical Regions of Canada Grade 5 Social Studies

Interior Plains: Land of Open Skies

GENERAL INFORMATION The Plains region is in between the Cordillera and the Great Canadian Shield. It is found in the Yukon, Northwest Territories, British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

Sometimes, people make the mistake of calling the Plains the Prairie Provinces or just the Prairies. The term prairie refers to the prairie grasses that grow wild in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

The Interior Plains landscape includes much more than just the prairie grasslands. You'll find that this entire region is generally flat in elevation.

Just as in the Cordillera, the human population tends to be greater in the southern region of the plains, but you'll also notice that town and cities generally are beside a water source like a lake or river. The Plains truly rely upon water, for the region's climate is generally dry.

Water not only helps irrigate crops and livestock but it is also a source of transportation for our products, supplies, goods and services. In the past, these water routes were also major fur trading routes. Similar to the Cordillera, these waterways also act as areas of recreation, tourism, as well, as resources like hydro-electricity for Canadians.

Each city in the Interior Plains offers its own unique industries, services and resources. Yet, it is important to discuss major industries found within this landscape. First of all, the farming is extremely important. Crops such as wheat, barley, oats, flax, canola, mustard, potatoes, corn and sugar beets are grown in the plains.

Farmers also raise cattle, pigs, poultry, to name a few. Both the crops and livestock produced in this area, feed many Canadians, as well as, others around the world. Moreover, the agricultural industry is also linked with promoting the tourism industry. Many rodeos, stampedes and agricultural shows are held throughout this region for everyone to enjoy.

Secondly the mining of fuel products like oil, natural gas, coal , potash copper, zinc, gold and uranium is crucial. Here Canadians take these resources that lie below the Plains and refine or make these resources into other products that all Canadians need on a daily basis.

_______________________________________________________________

To drive across the Prairies is to see endless fields of wheat and canola ripening under a sky that seems to go on forever. The plains of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba are among the richest grain-producing regions in the world.

Yet even here are surprises. If you leave the road at Brooks, Alberta, and drive north, you descend into the Red Deer River valley. Here, in desert-like conditions, water and wind have created strange shapes in the sandstone called "hoodoos." The same forces of erosion have uncovered some of the largest concentrations of dinosaur fossils in the world.

Alberta is Canada's leading producer of petroleum. The sedimentary rocks underlying the Prairies have important deposits of oil, natural gas and potash.

Source: Knight's Canadian Info Collection

Back to Social Studies

Back to Regions Index

Lastly many of the forest areas found in the Plains are harvested for the lumber industry or else admired by tourists for the tourism industry. The resources found in the Interior Plains are transported across Canada to other regions.

Since most of the Interior Plains are flat, transportation of goods and services is easily done by trains, pipelines, trucks, and planes. In other words, the Interior Plains supply a very important link for all Canadians and their economic development.

Source: The Physical Regions of Canada

Pipeline Map - Click for Larger Version

Explore the Regions - Video Tours

Interior Plains

Alberta | Saskatchewan

Manitoba | NWT

Interior Plains: Amazing Race Roadblock & Detour

World's Facts

World's Interesting Facts

18 Interesting Facts about Interior Plains Canada

Home » Regions » 18 Interesting Facts about Interior Plains Canada

Dan November 19, 2023

The Interior Plains of Canada form a significant geographic region within the country, extending across vast expanses of the central provinces. This expansive area is characterized by its relatively flat terrain, interrupted by low hills, river valleys, and occasional escarpments. It spans across Alberta , Saskatchewan , Manitoba , and parts of the Northwest Territories, covering a substantial portion of the central Canadian landscape.

The Interior Plains are part of the larger North American Interior Plains, which stretch from the Gulf of Mexico to the Canadian Arctic. In Canada , this region serves as a transitional area between the Rocky Mountains to the west and the Canadian Shield to the east, displaying a varied topography shaped by geological processes over millennia.

Geologically, the plains are composed of sedimentary rock formations, shaped by ancient seas, glaciers, and rivers. The region’s soils are generally fertile, supporting extensive agricultural activities that contribute significantly to Canada’s food production. The fertile lands of the Interior Plains are vital for grain farming, livestock grazing, and other agricultural practices, making it a key contributor to the nation’s economy.

The area is intersected by several major river systems, including the Saskatchewan River, Red River, and the North and South Saskatchewan Rivers, among others. These waterways have historically played a crucial role in transportation, trade, and settlement within the region, fostering the growth of cities and towns along their banks.

The Interior Plains of Canada exhibit a diverse ecosystem, supporting a variety of wildlife such as bison, deer, and numerous bird species. Human settlement and indigenous communities have long thrived in these regions, historically relying on the land for sustenance, trade, and cultural practices. Today, the Interior Plains remain a vital economic and cultural hub within Canada, balancing agriculture, industry, and natural landscapes that continue to shape the nation’s identity and heritage.

Grasslands National Park

Here are 18 interesting facts about Interior Plains of Canada to know more about it.

- Size and Scope: The Interior Plains of Canada cover a vast expanse, extending over 1.8 million square kilometers, encompassing significant portions of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba.

- Prairie Provinces: These plains are integral to the Prairie Provinces, known for their extensive agricultural lands and vibrant rural communities.

- Fertile Soil: The rich and fertile soils of the Interior Plains support diverse agricultural activities, including wheat, barley, canola, and livestock grazing.

- Bison Herds: Historically, immense herds of bison roamed these plains, sustaining indigenous cultures and being integral to the region’s ecosystems.

- Oil Reserves: The Interior Plains hold significant oil reserves, particularly in Alberta, making it a key contributor to Canada’s oil production.

- Natural Gas: Besides oil, substantial natural gas reserves lie beneath these plains, furthering the region’s importance in energy production.

- Grain Belt: The Canadian Prairies are part of North America’s Grain Belt, renowned for their prolific grain production, contributing to global food supplies.

- Glacial Features: Evidence of past glacial activity is visible across the plains, with features like drumlins, eskers, and moraines dotting the landscape.

- River Systems: Major rivers, such as the Saskatchewan, Red, and Assiniboine Rivers, traverse these plains, facilitating transportation and supporting agriculture.

- Grasslands National Park: Located in Saskatchewan, Grasslands National Park protects a unique prairie ecosystem, showcasing the diverse flora and fauna of the region.

- Human History: Indigenous peoples, including the Cree, Blackfoot, and Assiniboine, historically inhabited and traversed these plains, leaving a rich cultural legacy.

- Winnipeg: The city of Winnipeg, situated in the Interior Plains, serves as a prominent cultural and economic center within the region.

- Tornado Alley: Portions of the Interior Plains fall within Canada’s “Tornado Alley,” experiencing tornadoes due to unique atmospheric conditions.

- Prairie Dog Towns: Prairie dog colonies once thrived in these plains, creating extensive underground tunnel networks and supporting various other species.

- Natural Beauty: The Interior Plains boast stunning natural landscapes, including expansive grasslands, rolling hills, and picturesque river valleys.

- Protected Areas: Alongside Grasslands National Park, several provincial parks and conservation areas preserve the natural beauty and biodiversity of these plains.

- Cultural Diversity: The Interior Plains exhibit a blend of cultures, reflecting the contributions of indigenous communities, European settlers, and immigrant populations.

- Economic Contribution: Beyond agriculture and energy, the Interior Plains contribute to industries like mining, forestry, and manufacturing, diversifying the region’s economy.

The Interior Plains of Canada stand as a testament to the nation’s geographical diversity and economic vitality. Spanning vast stretches of fertile lands, these plains have long been the heart of agricultural production, supplying the nation and the world with grains, oilseeds, and livestock. Beyond their agricultural significance, these plains hold treasures of natural resources, including oil, natural gas, and minerals, contributing significantly to Canada’s energy and resource sectors. Embracing a blend of rich indigenous heritage, diverse wildlife, and expansive landscapes, the Interior Plains encapsulate the spirit of resilience and adaptation, a testament to the continuous interplay between humans and the land. As they evolve in tandem with modern advancements and environmental consciousness, these plains remain a cornerstone of Canada’s identity, a cradle of cultures, and a thriving hub of economic activity amid their picturesque vistas and sprawling prairies.

← Previous post

Next post →

Related Posts

Porcupine Hills Provincial Park

What's Nearby

For park conditions, advisories or to book a campsite, see our RESERVATION SITE

Porcupine Hills is Saskatchewan’s newest provincial park, officially designated in 2018. Located southeast of the Town of Hudson Bay, Porcupine Hills Provincial Park boasts great camping, hunting and fishing. Snowmobiling and other winter activities are popular throughout the winter months. Porcupine Hills is a place like none other to relax, enjoy the scenery, or simply walk or hike. The park is made up of five existing provincial recreation sites including McBride Lake, Saginas Lake, Pepaw Lake, Parr Hill Lake and Woody River. The park’s focus is on protecting the region’s natural landscapes and ensuring the cultural values of the land are conserved. In this newly designated park, hunting and fishing will continue to be managed as they have been in previous years, campgrounds will stay small and simple, and First Nations and Métis people will continue to celebrate their cultures and carry out traditional use activities.

- MAPS & DOCS

Rates & Discounts

Camping available from May long weekend to Sep 30.

- See Park Fees

- Country / Rural

- Firewood - free

- Boat launch

- Fish cleaning facility

- Non-electric sites

- Picnic area

- Picnic tables

- Snowmobiling

Fish Species

- Northern pike

- Yellow perch

Inclusive Travel

- Pet friendly

VIEW NEWS FOR ALL PARKS

VIEW ALL PROVINCIAL PARK EVENTS

Related Documents

Contact Info

Email: [email protected]

- Phone: 306-865-4403 (Park Office)

- Mailing Address: Box 451, Porcupine Plain, SK, S0E 1H0

Campsite Reservation Service

- Phone: 1-855-737-7275

- Website: Book Now

Saskatchewan Provincial Park Info

- Email: [email protected]

- Phone: 1-800-205-7070

Location Info

View on map >

lat. 52.483897° N, long. -101.727254° W

Operation Hours

Phone: 306-865-4403 (Park Office) | 1-833-757-7275 (Campsite Reservation Service) | 1-800-205-7070 |

Update Location

Modifying your location may alter your results and options available.

Search Kids Discover Online's Library of Content

- American History

- Earth Science

- Historical Figures

- Life Science

- Physical Science

- Space Science

- World History

- Infographics

- Lesson Plans

The Interior Plains

- from U.S. Landscapes

Lexile Levels

As you look around, what do you see? It seems like the road stretches on for miles in both directions.

On either side of it, tall stalks of golden wheat sway in the wind. Now that you’ve left the land of hills and dense forests, you're near the exact center of the country. It's so flat here, a barn is the tallest thing around. Welcome to the Great Plains, the western region of the Interior Plains. It's not all flat, though – the Great Plains stretch all the way back to the edge of the Ozark Plateau, where you crossed low mountains. From here, though, all you can see is the line where land meets sky, way off in the distance.

Login or Sign Up for a Premium Account to view this content.

Next topic in u.s. landscapes, how astronauts see the states.

U.S. Landscapes

This is my alert message

- Skip to main content

- Skip to "About government"

Language selection

- Français

Caribou from the Tonquin herd in Jasper National Park, Alberta

National Parks System Plan

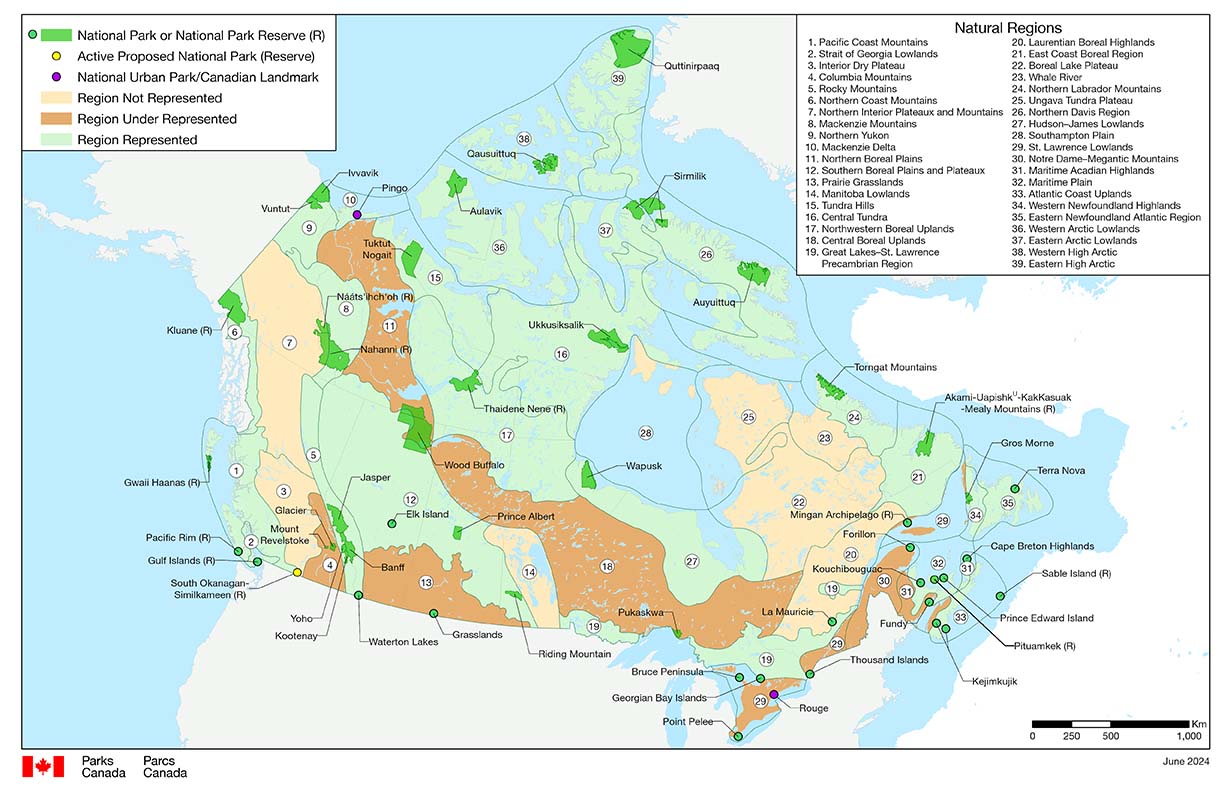

On this page:, understanding and appreciating, map of national parks and national park reserves in canada.

National parks are among the world's natural jewels. They represent the power of Canada's natural environment which has shaped not only the geography of this country, but also the course of its history and the experiences of the people who live and travel here.

National parks are established to protect and present outstanding representative examples of natural landscapes and phenomena that occur in each of Canada's unique natural regions, as identified in the National Parks System Plan. When establishing new parks, other considerations include the area’s ecological connectivity with other regions and whether the area is represented or underrepresented within the system plan.

These wild places, located in every province and territory, range from mountains and plains, to boreal forests and tundra, to lakes and glaciers, and beyond. National parks protect the habitats, wildlife, and ecosystem diversity representative of these natural regions.

National parks are located on the Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic coasts, across the interior mountains, plains and Great Lakes. They range in size from 14 km2 (Georgian Bay Islands National Park of Canada) to almost 45,000 km2 (Wood Buffalo National Park of Canada). And they include world-renowned names such as Banff and Jasper, as well as more recently established Ivvavik and Vuntut.

Parks Canada is responsible for both protecting the ecosystems of these magnificent natural areas and managing them for visitors to understand, appreciate, and enjoy in a way that doesn't compromise their integrity.

The breathtaking scenery and natural surroundings of national parks provide the perfect setting for tuning into nature, respecting it, and pledging to protect it. Each national park is a haven for the human spirit.

National parks tell the stories of the natural beginnings of these lands--mountains forming, lakes emerging, rivers running, forests growing, glaciers moving, grasslands evolving. They reveal ongoing natural processes--floods, fires and the migration of species. They provide opportunities to connect with nature, people and the events that define the peoples of these lands.

Visitors can paddle down rivers flowing through canyons carved over thousands of years, observe birds as they rest in their travels along traditional migration routes, walk through vibrant young forests transformed by fire. These are unforgettable experiences, made all the more memorable by the rich experiences Parks Canada offers.

Parks Canada is working to maintain or restore the ecological integrity of national parks. This means keeping ecosystems healthy and whole—a state where ecosystem biodiversity, structures and functions are unimpaired and likely to persist.

The national parks of Canada are a source of pride for Canadians and an integral part of our identity, they celebrate the beauty and infinite variety of this land.

The National Parks System Plan identifies each of Canada's unique natural regions. The aim of the plan is to protect a representative sample of each of these landscapes. This framework has helped guide the expansion of the parks system for decades.

Additional considerations

When evaluating a new area as a candidate site, a range of factors are examined, including:

- areas of cultural significance

- underrepresented natural regions in the system

- biodiversity and ecological processes

- landscape connectivity

- support of Indigenous communities and governments

- support of any relevant provincial or territorial governments

To request a PDF copy of the National Park System Plan (1997), please contact us at: [email protected] .

Read more about creating new national parks

The map below identifies the terrestrial regions of Canada. It also notes whether these regions are represented by a national park, or are underrepresented.

This is a map of the country of Canada, divided into provinces, territories, and natural regions. The general purpose of this map is to identify the 39 terrestrial regions of Canada including whether or not they are presently represented by a national park or national park reserve.

The map contains a legend in the top left corner, another legend in the top right corner, and a 0 to 1200 kilometre scale in the bottom right. The year 2024 is indicated outside the bottom right corner while the Parks Canada government of Canada logo is positioned in bottom left.

A green line encircles the entire country of Canada on land and in Canadian waters, indicating the country’s established marine and terrestrial boundaries. This line also separates Canada from neighbouring countries, the United States and Greenland, and also separates Canadian waters from international waters. International waters are found west of British Columbia; north of Yukon Territory; north-west of the North West Territories; north-east and east of Nunavut; north and north-east of Labrador; north east and east of Newfoundland; and east of Nova Scotia.

This same green line is used to divide Canada into 39 distinct terrestrial regions. These boundaries range in scale and may include parts of one or more provinces and territories. Within each of these 39 boundaries is a number, listed from 1 to 39. On the legend in top right hand corner, these numbers are also listed, corresponding to the unique name for each region.

Each terrestrial region is also colour coded to indicate that region’s current level of representation within the National Parks System Plan. The corresponding legend in the top left hand corner of the map indicates that the regions appear in one of beige, light brown, or light green colours. Green indicates that the region is represented within the current National Parks System Plan. Brown indicates that the region is underrepresented. Beige indicates that the region is not represented within the System Plan.

This same legend also indicates that dark green forms appears on the map in places where there are existing national parks or national park reserves. This dark green appears as small green circles for smaller parks or larger shapes for larger parks. The legend also indicates that small yellow circles appear on the map in locations where there is an active proposal for a new national park or national park reserve. Lastly, the legend indicates that small purple circles appear on the map in places where there is a national urban park or a Canadian landmark.

The following is a description of each of Canada’s 39 terrestrial regions, including the region’s boundaries; the region’s corresponding number within the top right legend; the region’s level of representation in the System Plan; and the details of any indicated national parks, national park reserves, national urban parks, Canadian landmarks, or active proposals in each region.

Canada's 39 terrestrial regions are divided into eight regional groups on this map. The first group is the Western Mountains, found in British Columbia and Yukon Territory.

In the Western Mountains, there are:

1. Coast Mountains , region 1 – indicated as represented in the National Park System Plan. This region includes Pacific Rim National Park Reserve, in south west Vancouver Island, and Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve, in the Haida Gwaii archipelago.

The green line boundary for region-1 includes: the northern section and most of the central section of Vancouver Island, Haida Gwaii archipelago, all of coastal B.C. from south of the Johnstone Straight as far north as the Alaskan coast, and an inland section including parts of the West Coast region and South Coast region, extending south-east to the United States border.

2. Strait of Georgia Lowlands , region 2 – indicated as represented in the National Park System Plan. This region includes Gulf Islands National Park Reserve, south-east of Vancouver Island.

The green line boundary includes the southern tip of Vancouver Island, parts of Eastern Vancouver Island, and extends north of the town of Courtenay, beyond the Georgian Straight to just south of the Johnstone Straight. The boundary extends southward and eastward, including portions of the South Coast region. It then extends eastward to include a small segment of the B.C. Interior, along the Unites States Border, including the south part of Harrison Lake and a small segment eastward of this lake.

3. Interior Dry Plateau , region 3 – indicated as not represented. A yellow dot indicates an active proposed national park reserve in South Okanagan-Similkameen, found in the south eastern mainland region of British Columbia.

Region 3’s green line shares its western boundary with the eastern boundary of Region 1. The northern boundary is shared with the southern boundary of Region 7, running southward and eastward across Central B.C., as far east as the Alberta border. The boundary then curls southward toward the United States border, and west of Lake Revelstoke.

4. Mountains , region 4 – indicated as under represented. This region includes Mount Revelstoke National Park, and Glacier National Park, both found near the B.C.-Alberta border.

The green line boundary of Region 4 shares the entirety of its western boundary with the south-east boundary of Region 3, then runs south-east along the United States border. Region 4 then gradually veers north-west just past Lake Koocanusa. The boundary runs north-west past Mount Revelstoke National Park and Glacier National Park, and gradually bends west alongside Kinbasket Lake, it then curves west just past the point where the Alberta border sharply veers north-east.

5. Rocky Mountains , region 5 – indicated as represented; includes the following national parks, from south to north: Waterton Lakes, Kootenay, Banff, Yoho, and Jasper. All five are found near the B.C.-Alberta border in the south-west area of Alberta.

The green line boundary of Region 5 shares its western boundary with 3 different Regions; the south-eastern boundary of Region 7 starting near the Yukon-B.C. border, gradually curving south-east along Region 3’s north-east boundary, continuing south-east along Region 4’s east boundary until reaching the United States border. Region 5’s boundary stretches south-east across the B.C.-Alberta border, past Waterton Lakes and extends north past Calgary, sharing its boundary line with Region 13’s western boundary. The north-easterly boundary, shared with Region 12, curves north-west above Jasper and crosses west over the B.C.-Alberta border extending until reaching the southern border of Region 8, near the Yukon-B.C. border. Region 5 shares its northern boundary line with Region 8’s south boundary line.

6. Northern Coast Mountains , region 6 – indicated as represented. This region includes Kluane National Park Reserve, found in the furthest south-west corner of Yukon Territory.

Region 6’s north-west green line boundary begins in the south-west corner of Yukon Territory near Beaver Creek, extending south along the United States Alaskan border, past the B.C.-Yukon border until reaching the north-west boundary of Region 1. The south-west boundary of Region 6 is shared with Region 1’s north-east boundary line, beginning at the Pacific Ocean’s coast, then curving north-east along the Skeena River. Sharing its eastern boundary line with Region 7, Region 6’s eastern limit gradually extends north-west, past the Yukon-B.C. border, and north west, until again reaching the Alaskan border, near Beaver Creek.

7. Northern Interior Plateaux and Mountains , region 7 – indicated as not represented. This region includes a portion of Nááts'įhch'oh National Park Reserve, found close to the Yukon-Northwest Territory border, in the eastern portion of this region, as well as the western portion of Nahanni National Park Reserve, found immediately south of Nááts'įhch'oh along this same border.

Region 7’s green boundary line begins along the northern midwest Yukon-Alaska border; the west boundary line is shared with Region 6 and the north-east corner of Region 1. The southern boundary is shared with Region 3’s northern green line, extending south-east towards the north-west corner of Region 5. Region 7 shares its south-east boundary line with Region 5, curving north-west up to the Yukon-B.C. border. Then curving east over the Yukon-Northwest Territory border, the boundary line goes through Nááts'įhch'oh National Park Reserve then back over the Yukon-Northwest Territory border along its eastern boundary line, which abuts against Region 8’s western boundary. Region 7’s north-west corner is shared with the south-west corner of Region 9, extending north-west to the Yukon-Alaska border.

8. Mackenzie Mountains , region 8 – indicated as represented. Region 8 includes a portion of Nááts'įhch'oh National Park Reserve as well as a large portion of Nahanni National Park Reserve, found immediately south of Nááts'įhch'oh along this same border.

The western green line boundary for Region 8 is shared with the north-east corner of Region 7’s boundary line, found close to the B.C.-Yukon border, beginning in north-east B.C. Region 8’s south boundary line extends south-east along Region 5’s northern boundary line towards Region 12’s north-west boundary line. Curving north-east over the B.C.-Yukon, Yukon-Northwest Territory borders and around Nahanni National Park Reserve, Region 8’s eastern boundary line is shared with Region 11, following the Mackenzie River. Just past Great Bear Lake, the boundary line extends north-west over the Yukon-Northwest Territory border, towards the north-west corner of Yukon, then making a slight curl south-west where it meets the north and north eastern boundaries of Region 7

9. Northern Yukon , region 9 – indicated as represented. Situated in northern Yukon, Region 9 includes Vuntut National Park and, immediately north, a large portion of Ivvavik National Park.

Region 9’s western green line boundary begins at the northern tip of Region 7’s boundary line, extending along the Yukon-Alaska border, past Vuntut and Ivvavik, until meeting the Beaufort Sea coast. Cutting along the north-eastern edge of Ivvavik, Region 9’s north-eastern boundary, shared with Region 10’s south-west boundary, extend south-east towards the Yukon-Northwest Territory border, curving south-west near a cluster of lakes situated around the Mackenzie River, in the north-west corner of the Northwest Territories. Running along Region 11’s north-west corner, Region 9’s south-east boundary line curves over the Yukon-Northwest Territory border towards Region 8’s north-west corner. Extending along Region 8’s north-west boundary line, Region 9’s south boundary curves north-west towards the Yukon-Alaska border.

In the Interior Plains, there are:

10. Mackenzie Delta , region 10 – indicated as represented. Region 10 includes a small portion of Ivvavik National Park, situated in northern Yukon, as well as Pingo Canadian Landmark, found in the north-west corner of the Northwest Territories.

Region 10 shares its western green line boundary with Region 9’s north-eastern boundary, found near the ocean coastline along the Yukon-Northwest Territory border. Region 10’s southern boundary begins just west of the Mackenzie river, heading north-east through a cluster of small lakes to meet the Beaufort Sea and beyond toward Banks Island. The north boundary line starts north-west of Banks Island, extending west along the coast extending west before meeting the Yukon-Alaska border.

11. Northern Boreal Plains , region 11 – indicated as under represented. Region 11 includes a large portion of Wood Buffalo National Park, situated around the Alberta-Northwest Territory border.

Region 11’s north-western boundary cuts south-west through a cluster of lakes near the south-east boundary of Region 10, extending from the west corner of the Northwest Territories and continuing over the Yukon-Northwest Territory border, alongside Region 9’s eastern boundary. Curving back across this same border, Region 11’s western boundary is shared with Region 8’s north-east boundary line extending south-east towards Great Bear Lake. This western line then arches south-west towards Nahanni National Park Reserve, including a small portion of Nahanni. before stopping near the Yukon- Northwest Territory border. The southern green boundary line travels south-east along the provincial-territory border towards Wood Buffalo National Park. Crossing the Alberta-Northwest Territory border, Region 11’s south-east boundary line then extends through a large portion of Wood Buffalo National Park, beginning in the Northwest Territory and extending to the north-east corner of Alberta. Curving north around Lake Claire, Region 11’s east boundary continues north, back over the Alberta-Northwest Territory border, passing northwest across Great Slave Lake and Great Bear Lake, and sharing eastern and north-eastern boundary lines with Region 17 and Region 15.

12. Southern Boreal Plains and Plateaux , region 12 – indicated as represented. Region 12 includes Elk Island National Park, situated in central Alberta; Wood Buffalo National Park in north-east Alberta; Prince Albert National Park in central Saskatchewan; and Riding Mountain National Park, in the south of Manitoba.

Region 12’s green line boundary includes parts of four provinces and two territories. Beginning at the south-east corner of the Yukon, Region 12’s north-west corner shares its boundary lines with Region 8, Region 5 in B.C., and Region 11 in the Northwest Territory and Alberta. Extending south-east, Region 12’s shared boundary line with Region 5 continues over the B.C.-Alberta border towards Red Deer. Sharing its south boundary line with Region 13’s northern boundary, Region 12’s boundary line extends east over the Alberta-Saskatchewan border and heads south-east towards and across the Saskatchewan-Manitoba border. Region 12’s south-east corner boundary lines are along the Manitoba-U.S. border and Region 14’s boundary line, found in the south of Manitoba. Extending north-west past and around Riding Mountain National Park, back over the Saskatchewan-Manitoba, Region 12’s east boundary line, shared with both Region 14 and Region 18, continues through central Saskatchewan and heads north-west towards the western edge of Lake Athabasca, in the north-east corner of Alberta. Cutting through part of Wood Buffalo National Park, Region 12’s boundary line, shared with Region 11, crosses the Alberta-Northwest Territory border and continues north-west towards Nahanni National Park Reserve.

13. Prairie Grasslands , region 13 – indicated as under represented. Region 13 includes Grasslands National Park, situated in south-west Saskatchewan, near the U.S. border.

Region 13’s south green line boundary begins just east of Waterton Lakes National Park, situated in Alberta, and travels east along the Alberta-U.S. border, continuing over the Alberta-Saskatchewan border, and the Saskatchewan-Manitoba border. Gradually curving north-west around Winnipeg, Region 13’s northern boundary, shared with Region 12’s southern boundary, arches north near Regina, then arches south-west around Saskatoon. Making its way back over the Saskatchewan-Alberta border, Region 13’s northern boundary meets with Region 5’s eastern boundary line near Calgary, and then extends south to the Alberta-U.S. border.

14. Manitoba Lowlands , region 14 – indicated as not represented. Situated in central Manitoba and near the Saskatchewan-Manitoba border, Region 14 does not include any national parks.

Region 14 shares its western boundary with Region 12’s eastern boundary, found in the south-west corner in Manitoba. Extending north-west towards the Saskatchewan border, Region 14’s western boundary arches north-east around Lake La Rouge, reaching Region 18’s south-west boundary, near the Saskatchewan-Manitoba border. Crossing the provincial line, Region 14’s north boundary continues east through a cluster of lakes, curling south around most of Lake Winnipeg. The south-eastern boundary, shared with Region 19, extends south until reaching the U.S.-Manitoba border.

In the Canadian Shield, there are:

15. Tundra Hills , region 15 – indicated as represented. Region 15 includes Tuktut Nogait National Park situated in the north of the Northwest Territories, along the Nunavut-Northwest Territories border. Region 15 also includes a small portion of Thaidene Nene National Park Reserve in the north-east part of the Northwest Territories.

Region 15’s north boundary, shared with Region 10, begins along the coast of the Beaufort Sea, in north-eastern Northwest Territories. Curving South-east, Region 15’s western boundary, shared with Region 11’s eastern boundary, extends towards Great Bear Lake, along the Northwest Territories-Nunavut border. Curving north over the territorial border with Nunavut border, then south-east back into the Northwest Territories, Region 15’s southern boundary runs south-east towards Thaidene Nene National Park Reserve. Region 15’s southern boundary is shared with Region 17’s northern boundary. Crossing through a small portion of Thaidene Nene, Region 15’s eastern boundary line, shared with Region 16, gradually curves north-west across the Northwest Territories-Nunavut border and continuing north through Bathurst Inlet. Following the coast line north-west through the Coronation Gulf and near Victoria Island, the line runs across the Amundsen Gulf and across the Northwest Territories-Nunavut border again. Region 15’s eastern boundary, shared with Region 36’s south boundary, joins its own northern boundary near Banks Island.

16. Central Tundra , region 16 – indicated as represented. Region 16 includes Ukkusiksalik National Park in the south-east of mainland Nunavut, just west of Southampton Island and the Hudson Bay. Region 16 includes a small portion of Thaidene Nene National Park Reserve, found situated in the north-east of the Northwest Territories.

Region 16’s north boundary begins near Bathurst Inlet on Nunavut’s mainland. Extending east, following the mainland coastline, Region 16’s north boundary line, shared with Region 36 and 37, curves north towards the Queen Elizabeth Islands. Passing through a portion of Prince of Wales Island, Region 16’s northern boundary line extends south through Somerset Island, continuing near Fort Ross, then Kuggaruk, until arching north towards Baffin Island along the Gulf of Boothia. Curving south-east through the south-west portion of Baffin Island, Region 16’s boundary arches south through the north-eastern mainland of Nunavut towards the Northwest Passages. Sharing its north-east boundary line with Region 26, Region 16’s boundary line continues through the Foxe Channel near north-western Quebec, curving around a cluster of islands north of the Hudson Bay, and extending west through Southampton Island and continuing until the central-east Nunavut coastline, just east of Ukkasiksalik National Park. Stretching south along the north-west coastline of the Hudson Bay until close to the Nunavut-Manitoba border, Region 16 shares its eastern boundary with Region 28. Region 16’ssouthern boundary, shared with Region 17, begins near the Nunavut-Manitoba border, then continues north-west over the Nunavut-Northwest Territories border, close to Dubawnt Lake. This boundary line then curves north-east back over the territorial border then arches south-west near Nunavut’s Aberdeen Lake crossing yet again over the territorial border. Region 16’s southern boundary extends towards Thaidene Nene National Park Reserve situated in eastern Northwest Territory before meeting the region’s western boundary, shared with Region 15’s eastern boundary. This line runs north where it connects with Region 15’s northern boundary.

17. Northwestern Boreal Uplands , region 17 – indicated as represented. Region 17 includes a large portion of the Thaidene Nene National Park Reserve, situated in the north-east of the Northwest Territories.

Beginning near Great Bear Lake, Region 17’s western boundary extends south-east along Region 11’s eastern boundary, past Yellowknife, through Great Slave Lake, then over the Northwest Territories-Alberta border, continuing towards Lake Athabasca. Bending north-east over the Alberta-Saskatchewan border, then south near the Saskatchewan-Northwest Territories border, Region 17’s south boundary runs south-east through Reindeer Lake. Continuing over the Saskatchewan-Manitoba border, is boundary, shared with Region 18’s northern boundary, extends east through northern Manitoba towards the town of Gillam. Curving north towards Churchill, Region 17’s eastern boundary line follows the Manitoba-Nunavut border along the Hudson Bay coast, then arches north-west through south-west Nunavut. Region 17’s northern boundary extends north-west over the Nunavut-Northwest Territories border near Dubawnt Lake, then arches north again over the territorial border and back again, continuing north-west and cutting through the northern tip of Thaidene Nene National Park Reserve. Region 17’s northern boundary, shared with both Regions 15 and 16, continues further north, once more over the Nunavut-Northwest Territory border, then arching south-west back over the border towards Great Bear Lake.

18. Central Boreal Uplands , region 18 – indicated as under represented. Region 18 includes Pukaskwa National Park, situated along a portion of coastal Lake Superior.

Region 18’s boundary crosses through parts of five provinces: north-east Alberta, northern Saskatchewan, central Manitoba, northern Ontario, and south-western Quebec. Beginning in northern Alberta, just east of Wood Buffalo National Park, Region 18’s western boundary line crosses the Alberta-Saskatchewan border, curving south-east along Region 12’s shared boundary line, over the Saskatchewan-Manitoba border, towards Lake Winnipeg. Extending south along Lake Winnipeg, Region 18’s western boundary line, shared now with Region 14, continues south-east. East of Winnipeg, Region 18’s southern boundary extends east over the Manitoba-Ontario border, towards Lake Superior. Following the Lake Superior coast, Region 18’s south boundary line shared with Region 19, extends east through Wawa, arching south-east above Sudbury, then continuing east over the Ontario-Quebec border near Kirkland Lake. Curving north-east through south-west Quebec, Region 18’s east boundary line, shared with Region 20, extends north towards Lake Mistassini. Just south of Lake Mistassini, Region 18’s northern boundary, shared with Region 22, curves gradually south-west over the Quebec-Ontario border, near James Bay. Region 18’s northern boundary, shared with Region 27, arches north-west past Fort Hope, then over the Ontario-Manitoba border, curving west just south of Wapusk National Park in northern Manitoba. Sharing its northern boundary line with Region 17, Region 18’s boundary line continues over the Manitoba-Saskatchewan border near Reindeer Lake, then arches north-west through Lake Athabasca, crossing the Saskatchewan-Alberta border.

In the Great Lakes – St. Lawrence Precambrian Region, there are:

19a. West Great Lakes – St. Lawrence Precambrian Region , region 19a – indicated as represented. Region 19a does not include any national parks situated in north-west Ontario, along the U.S. border and the Manitoba border.

Region 19a’s northern boundary, shared with Region 18’s south-west boundary line, begins in the south-east corner of Manitoba near Winnipeg, curving north-east over the Manitoba-Ontario border, then continuing above Lake of the Woods and Eagle Lake towards Thunder Bay. Region 19a’s eastern boundary line extends south along the Lake Superior coast until hitting the Ontario-U.S. border. Its southern boundary line runs along the U.S.-Ontario border, then crosses the provincial Ontario-Manitoba border and extending west, south of Winnipeg. Region 19a’s western boundary line begins at the U.S-Manitoba border and extends north near Winnipeg.

19b. Central Great Lakes – St. Lawrence Precambrian Region , region 19b – indicated as represented. Region 19b includes Georgian Bay Islands National Park in southern Ontario on the coast of the Georgian Bay; Thousand Islands National Park in eastern Ontario, along the St. Lawrence River; and La Mauricie National Park in south-eastern Quebec.

Region 19b’s western green line boundary begins near Wawa, following Lake Superior’s coastline south-east through Sault Ste. Marie, then along the U.S.-Ontario border near St. Joseph Island. Extending east along the Lake Huron coastline, through Georgian Bay Islands National Park, Region 19b’s southern boundary, shared with Region 29, continues east through Kingston. Running north along the Thousand Islands National Park along the St. Lawrence River near Kingston, Region 19b’s eastern boundary line curves north-west towards Ottawa, over the Ontario-Quebec border. The boundary curves north-eastward beyond Montreal, past Trois-Rivières, and extending north-east past Quebec City. Region 19b’s northern boundary, shared with Regions 20 and 18, curves south-west north of La Mauricie National Park, and continues west across southern Quebec. This north boundary arches north-west near Lake Simard, crossing over the Quebec-Ontario border, arching south-west past Biscotasing, and extending west towards Lake Superior, near Wawa.

19c. East Great Lakes – St. Lawrence Precambrian Region , region 19c – indicated as represented. Situated in south-eastern Quebec west of the St. Lawrence River, Region 19c does not include any national parks.

Region 19c northern green line boundary begins at the St. Lawrence river, extending west along the Saguenay River, arching south around Lac Saint-Jean in central Quebec. Curving south and around the lake, Region 19c’s southern boundary line curls eastward and back towards the St. Lawrence River.

20. Laurentian Boreal Highlands , region 20 – indicated as not represented. Situated in south-east Quebec along the St. Lawrence River, Region 20 does not include any national parks..

Region 20’s southern boundary, shared with Region 19b, begins in south-western Quebec, curves south-east through Mont-Laurier, arching north-east above La Mauricie National Park, and continues north-east above Quebec City, towards the St. Laurence River. This boundary follows the St. Laurence coast northward, extending west near Malbaie, arching north, and then east around Lac Saint-Jean, before continuing east towards the Gulf of St. Laurence. Following Gulf’s coastline northward, and sharing its eastern boundary line with Region 29c, Region 20’s boundary line continues through Sept-Iles, just north of Mingan Archipelago National Reserve. Region 20’s northern boundary then arches north-west over the Quebec-Labrador border, continuing south-west over this same border once again. Extending south-west through Manicouagan Lake, past Mistassini Lake, then towards the Quebec-Ontario border, Region 20’s western boundary is shared with Region 21, 22 and 18.

21. East Coast Boreal Region , region 21 – indicated as represented. Region 21 includes Akami-Uapishk⋃-KakKasuak-Mealy Mountains National Park Reserve in the north-east corner of Labrador.

Region 21’s eastern boundary begins in north-eastern Quebec near Natashquan, extending north-east along the Gulf of St. Lawrence, over the Quebec-Labrador border, then towards the Labrador Sea. Arching north-west along the Labrador coast, Region 21’s northern boundary extends towards Hopedale. Curving south towards Michikamau Lake, Region 21’s western boundary line continues south-east past Churchill Falls, through Winokapaa Lake, then back over the Labrador-Quebec border. Curving north-east, Region 21’s southern boundary line crosses over the Quebec- Labrador border, then arches south-east back over the Quebec-Labrador border once more, extending towards the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

22. Boreal Lake Plateau , region 22 – indicated as not represented. Region 22 does not include any national parks in central Quebec and near the south-west of the Labrador-Quebec border.

Region 22’s western boundary, shared with Region 27’s eastern boundary, begins in the Hudson Bay, arching south-east through James Bay, curving south near Eeyou Istchee-James Bay, continuing towards Matagami. Region 22’s southern boundary, shared with Region 18, extends north-east towards Lake Mistassini. It then runs north-east across central Quebec, through Lake Manicouagan, and over the Quebec-Labrador border. Region 18’s eastern shared boundary with Regions 20 and 21, curves north-east along the Quebec-Labrador border in Newfoundland and Labrador, continuing towards Michikamau Lake. Curving west over the Quebec- Labrador border, Region 22’s northern boundary, shared with Regions 23 and 25, curves south-west over the provincial border, through Attikamagen Lake, then over the Quebec-Labrador once more. Curving north-west towards Ungava Bay, Region 22’s northern boundary curves south-west across north-western Quebec. Running north-west of Qullinaaq Lake, Region 22’s western boundary curves north around the lake, and arches south-west once again. Continuing past Lake Wiyâshâkimî, Region 22’s western boundary line continues through the Hudson Bay, near the mouth of the James Bay.

23. Whale River , region 23 – indicated as not represented. Region 23 does not include any national parks situated in northern Quebec, near the Quebec-Newfoundland and Labrador border.

Region 23’s western boundary, shared with Region 25’s eastern boundary, begins in north-western Quebec, in Ungava Bay. Region 23’s southern line curves south-east near Tasiujaq, continuing past Lake Le Moyne, then across the Quebec-Labrador border near Burnt Creek. Curving north-east through Attikamagen Lake, Region 23’s eastern boundary crosses back over the provincial border, extending northward towards the same border, further north-east. Region 23’s northern boundary, shared with Region 24’s southern line, gradually curves over the Quebec- Labrador border multiple times, extending north-west towards Ungava Bay, curving west above Akpatok Island.

24. Northern Labrador Mountains , region 24 – indicated as represented. Region 24 includes Torngat Mountains National Park situated in western Newfoundland and Labrador along the Labrador-Quebec border.

Region 24’s southern boundary, shared with Regions 22 and Region 23’s northern boundaries, begins just north of northern Quebec in Ungava Bay. Extending south-east inland to north-western Quebec, then across the Quebec- Labrador border, Region 24’s southern boundary arches north near the provincial border, above Michikamau Lake. Continuing north past Hopedale, Region 24’s eastern line, shared with Region 21’s western boundary, extends into the Labrador Sea just north of the coastline. Region 24’s northern boundary runs north-west of along the Labrador Sea coastline towards Resolution Island Nunavut, near Ungava Bay.

25. Ungava Tundra Plateau , region 25 – indicated as not represented. Situated in north-western Quebec near the Hudson Bay, Region 25 does not include any national parks.

Region 25’s northern boundary, shared with Regions 16 and 26’s southern boundaries, begins near Nottingham Island in Nunavut’s Foxe Channel, extending east through the Hudson Strait, then curving south through Ungava Bay. Continuing south-west past Tasiujaq, Region 25’s south-eastern boundary curves south-west across north-western Quebec. Running north-west of Qullinaaq Lake, this boundary line curves back north around the lake, and arches south-west once again. Continuing south past Lake Wiyâshâkimî, Region 25’s southern boundary continues through the Hudson Bay, just north of the mouth of the James Bay. Curving north-west through the Hudson Bay, the western boundary extends past Belcher Island, past Mansel Island, and towards the Foxe Channel.

26. Northern Davis Region , region 26 – indicated as represented. Region 26 includes Auyuittuq National Park, situated on Nunavut’s eastern island; as well as a large portion of Sirmilik National Park in north-east Nunavut.

Region 26’s southern green line boundary begins in the southern region of Foxe Basin, just north of Southampton Island. Extending east through the Hudson Strait towards Ungava Bay, Region 26’s southern boundary—shared with Regions 16, 25, 23, and 24--curves north-east, just south of Resolution Island. Arching north-west along Baffin Island through the David Strait, Region 26’s northern boundary curves north-west through Baffin Bay, extending north just past Devon Island. Curving south-west through the south-east portion of Ellesmere Island, Region 26’s western boundary continues south, passing through a small portion of Devon Island, through a large portion of Sirmilik National Park. This boundary extends south-east through part of Baffin Island near the northern portion of Foxe Basin, continuing south-east towards Iqaluit, then stretching west through Foxe Basin.

In the Hudson Bay Lowlands, there are:

27. Hudson–James Lowlands , region 27 – indicated as represented. Region 27 includes Wapusk National Park in north-eastern Manitoba.

Region 27’s north boundary begins in north-east Manitoba near Churchill on the Hudson Bay coast. Extending south-east past Wapusk National Park, this boundary line, shared with Region 28’s southern boundary, continues east over the Manitoba-Ontario border, towards James Bay. Near the mouth of the James Bay, Region 27’s east boundary curves south-east over the Ontario-Quebec border, towards La Grande Reservoir River in south-eastern Quebec. Arching south through Eeyou Istchee James Bay, Region 27’s east boundary runs towards Evan Lake. Region 27’s southern boundary, shared with Region 18’s northern boundary, extends west towards the Quebec-Ontario border just south of James Bay, gradually curving north towards the Ontario-Manitoba border, and arching north towards the Hudson Bay, just west of Wapusk National Park.

28. Southampton Plain , region 28 – indicated as not represented. Region 28 does not include any national parks on the Nunavut islands situated in the northern portion of the Hudson Bay.

Region 28’s western boundary begins along the Nunavut-Hudson Bay coast near Ukkusiksalik National Park in north-eastern Nunavut. This boundary follows the Hudson Bay coast south, across the Nunavut-Manitoba border, then curving south-east over the Manitoba-Ontario border. Region 28 shares its western and southern boundaries with Regions 16, 17, and 27. Region 28’s eastern boundary begins near the mouth of the James Bay, curling north-west towards Southampton Island. Sharing its northern boundary line with Region 16, Region 28’s boundary extends west through Southampton Island and towards Ukkusiksalik National Park in south-east Nunavut.

In the St. Lawrence Lowlands there are:

29a. West St. Lawrence Lowland , region 29a – indicated as under represented. Region 29a includes Bruce Peninsula National Park situated near Lake Huron and the Georgian Bay in south-central Ontario; the Georgian Bay Islands National Park in south-central Ontario; Point Pelee National Park in southern Ontario; as well as Rouge National Urban Park in south-eastern Ontario.

Region 29a’s southern boundary begins near St. Joseph Island, extending south-east along the Ontario-U.S. border through Lake Huron, then through Lake St. Clair. Continuing east along the Ontario-U.S. border, Region 29a’s south-eastern boundary passes through Lake Erie, then the Niagara River, continuing through Lake Ontario towards the St. Lawrence River. Region 29a’s north boundary line, shared with Region 19b, extends west near Kingston towards the Georgian Bay. Following the Georgian Bay coastline, Region 29a’s northern line continues west towards Sault Ste. Marie.

29b. Central St. Lawrence Lowland , region 29b – indicated as under represented. Region 29b includes a portion of Thousand Islands National Park in eastern Ontario, along the St. Lawrence River.

Region 29b’s southern green line boundary, shared with the northern U.S. border, begins in the St. Lawrence River just north of Kingston, near Thousand Islands National Park. Following the U.S.-Ontario border, Region 29b’s southern boundary line extends north-east along the St. Lawrence River, continuing over the Ontario-Quebec border near Cornwall. Region 29b’s eastern boundary begins at the U.S.-Quebec border, just east of Lake Champlain, and curves north-east past Sherbrooke towards Quebec City. Region 29b’s northern boundary, shared with Region 19b, begins near Quebec City extending south-west along the St. Lawrence River, and through Trois-Rivières. Continuing south-west just north of Montreal, this same boundary line crosses over the Quebec-Ontario border near Lachute along the Ottawa River. Crossing the Quebec-Ontario border once more, Region 29b’s boundary curves south-west just north of Gatineau, then arches south-east crossing once again over the Quebec-Ontario border and through the Ottawa River, just west of Ottawa. Arching south-east past Big Rideau Lake, Region 29b’s northern border continues south towards the St. Lawrence River.

29c. East St. Lawrence Lowland , region 29c – indicated as under represented. Region 29c includes Mingan Archipelago National Park Reserve in north-eastern Quebec, as well as a small portion of Gros Morne National Park on the island of Newfoundland.

Region 29c’s eastern boundary begins on the Strait of Belle Isle, extending south through the eastern portion of the Long Range Mountains, over a small portion of Gros Morne National park, continuing past St. Georges Bay, towards Cabot Strait. Extending west through the St. Lawrence River, Region 29c’s southern line continues west past Anticosti Island. Curving north-east, Region 29c’s western passes through Sept-Iles, extending north-east just north of Mingan Archipelago National Park Reserve, then continuing along the shoreline. This line continues over the Quebec- Labrador border, and back towards the Strait of Belle Isle.

In the Appalachian Region, there are:

30. Notre Dame-Megantic Mountains , region 30 – indicated as under represented. Region 30 includes Forillon National Park in eastern Quebec.

Region 30’s southern boundary begins east of Lake Memphremagog along the Quebec-U.S. border, following the border north and north-east, over the Quebec-New Brunswick border continuing east along the New Brunswick-U.S. border towards Grand Lake. Curving north-west, Region 30’s eastern boundary, shared with Regions 31 and 32, crosses through central New-Brunswick and continues north past Bathurst, arching west through Chaleur Bayan through the St. Lawrence River. Region 30’s northern boundary line, shared with Region 29c, curves south-west just south of Anticosti Island, extending along the St. Lawrence River. Following this river south, Region 30’s western boundary-- shared with Regions 20, 19c, 19b, and 29b-continues south towards Quebec City, curving east towards the U.S.-Quebec border near Lake Memphremagog.

In the Maritime Acadian Highlands, there are:

31a Maritime Acadian Highlands , region 31a – indicated as under represented. Region 31a includes Fundy National Park, situated in south-east New Brunswick, and part of Kejimkujik National Park, found in southern Nova Scotia

Region 31a’s western boundary begins in Chaleur Bay, curving south-east past Bathurst, across central New-Brunswick, continuing towards Grand Lake along the New-Brunswick-U.S. border. Following this same border, Region 31a’s south boundary continues east, passing south of Passamaquoddy Bay, passing over the Bay of Fundy, then extending south of Brier Island. This line extends north-east through south-western Nova Scotia, continuing through a portion of Kejimkujik, and north towards Truro. Region 31a’s northern boundary extends south-west along Minas Basin, then along the Cobequid Bay shoreline towards the Bay of Fundy. Curving north, this boundary continues towards Amherst, then crosses over the Nova Scotia-New-Brunswick border, arching south-west just north of Moncton. Continuing south-west, Region 31a shares its northern boundary with Region 32, and arches north-west just past Saint John, extending through Fredericton, then Doaktown, and continuing towards Chaleur Bay.

31b Maritime Acadian Highlands , region 31b – indicated as represented. Region 31b includes Cape Breton Highlands National Park situated on Cape Breton Island in northern Nova Scotia.

Beginning near Eden Lake, Region 31b’s eastern boundary curves north-east through Bras d’Or Lake, towards Sydney. Arching north-west along Cape Breton Island, Region 31b’s western boundary extends south-west through Northumberland Strait, continuing south of Ballantyne’s Cove, extending past Antigonish, towards Governor Lake.

32. Maritime Plain , region 32 – indicated as represented. Region 32 includes Pituamkek National Park Reserve, situated in north-western Prince Edward Island; Prince Edward Island National Park in central P.E.I; as well as Kouchibouguac National Park in eastern New Brunswick.

Region 32’s western green line boundary begins in the St. Lawrence River, near Anticosti Island. Curving south-east through Chaleur Bay, through Doaktown, then past Fredericton, this boundary line, shared with Region 31a, curls north-east near Saint John. Extending north, Region 32’s south-eastern boundary line curves east just north of Moncton, crossing the Nova Scotia- New-Brunswick border. Arching south towards Bay of Fundy, following Cobequid Bay and Minas Basin shoreline, the boundary continues north-east across the Northumberland Strait, arching east, just north of Cape Breton Island. Extending west, Region 32’s northern boundary continues across the Gulf of St. Lawrence and into the St. Lawrence River, just south of Anticosti Island.

33. Atlantic Coast Uplands , region 33 – indicated as represented. Region 33 includes a large portion of Kejimkujik National Park situated in southern Nova Scotia, and Sable Island National Park Reserve in eastern Nova Scotia.

Beginning in the Cabot Strait, Region 33’s western boundary extends south-west through Sydney, passing through Bras d’Or Lake and continuing south to Truro. Curving south-east, the western boundary extends through Windsor, continuing towards the Gulf of Maine. Arching north-east through the Atlantic Ocean, Region 33’s eastern boundary extends past Sable Island National Park Reserve found on Sable Island in the North Atlantic Ocean near Nova Scotia’s eastern shore. Curving north-west, Region 33’s eastern boundary continues towards the Cabot Strait, north of Cape Breton Island.

34. Western Newfoundland Highlands , region 34 – indicated as represented. Region 34 includes a large portion of Gros Morne National Park situated east on the island of Newfoundland.

Region 34’s western boundary begins just south of Goose Cove, extending south-west through a large portion of Gros Morne National Park, continuing south towards the Cabot Strait. Curving north-east through Cape Ray, Region 34’s eastern boundary passes through Red Indian Lake, then curving north-west through White Bay, across the Gulf of St. Lawrence, almost to the island of Labrador.

35. Eastern Newfoundland Atlantic Region , region 35 – indicated as represented. Region 35 includes Terra Nova National Park, situated in north-eastern Newfoundland and Labrador.

Region 35’s western boundary begins near Fox Harbour, extending south-east continuing through White Cove, crossing through central Newfoundland towards the Cabot Strait. Arching north-east towards Fortune Bay, Region 35’s southern boundary briefly follows the Newfoundland and Labrador- Saint Pierre border, continuing past Placentia Bay, towards St. John’s. Continuing past St. John’s towards Fox Harbour, Region 35’s northern boundary extends along the Newfoundland and Labrador coast.

In the Arctic Lowlands, there are:

36. Western Arctic Lowlands , region 36 – indicated as represented. Region 36 includes Aulik National Park situated in northern Northwest Territories.

Region 36’s northern boundary begins in the Beaufort Sea, extending south-east through the McClure Strait, over the Northwest Territories-Nunavut border, continuing past Bathurst Island towards the Parry Channel. Curving south through Prince of Wales Island, Region 36’s eastern boundary–shared with Regions 37 and 16--continues south, arching west just south of King William Island. Extending west through the Coronation Gulf, over the Nunavut-Northwest Territories border, Region 36’s southern continues through Amundsen Gulf, towards the Beaufort Sea. This boundary is shared with the boundary lines for Regions 16, 15 and 10, Curving north-east, Region 36’s western boundary extends north along Banks Island continuing towards the McClure Strait.

37. Eastern Arctic Lowlands , region 37 – indicated as represented. Region 37 includes a portion of Sirmilik National Park, situated in northern Nunavut, on part of the Queen Elizabeth Islands.

Region 37’s southern boundary—shared with Regions 16 and 26—begins near Prince of Wales Island, curving south-east through Somerset Island, continuing through the Gulf of Boothia. Arching north-east, Region 37’s southern boundary passes through Baffin Island’s western corner, curving south-east through Nunavut's mainland north-east corner, continuing through Foxe Basin, towards Iqaluit. Curving north-west past Amadjuak Lake, Region 37’s northern boundary, shared with Region 26, extends through Baffin Island along the Foxe Basin shoreline. Continuing north-west, the northern boundary passes through a large portion of Sirmilik National Park, near Baffin Bay. Extending west just south of Devon Island, Region 37’s northern boundary--shared with Regions 36, 38, and 39--continues through the Parry Channel, just past Somerset Island.

In the High Arctic Islands, there are:

38. Western High Arctic , region 38 – indicated as represented. Region 38 includes Qausuittuq National Park situated in the north-west of Nunavut, on part of the Queen Elizabeth Islands.

Region 38’s southern boundary—shared with Regions 36 and 37—begins in the Beaufort Sea, extending east through McClure Strait, over the Nunavut-Northwest Territories border, continuing past Bathurst Island towards the Parry Channel. Arching north-east near Cornwallis Island, Region 38’s eastern boundary crosses through a small portion of Devon Island, continuing north-east through the south-east portion of Ellesmere Island. Extending north-west, the northern boundary, shared with Region 39, curves north-west just south of Axel Heiberg Island, continuing towards the Arctic Ocean.

39. Eastern High Arctic , region 39 – indicated as represented. Region 39 includes Quttinirpaaq National Park situated in northern Nunavut, among the Queen Elizabeth Islands.

Region 39’s western green line boundary, shared with Region 38, begins in the Arctic Ocean just south of Axel Heiberg Island in northern Nunavut. Extending south-east through Meighen Island, Region 39’s boundary continues through the south-eastern portion of Ellesmere Island, curving south-west through the south-western corner of Devon Island, then continuing south along Cornwallis Island. Region 39’s southern boundary, shared with Region 37, extends east through the Parry Channel just north of Somerset Island. Curving north through Devon Island, then Jones Sound, the eastern boundary continues north-east through Ellesmere Island, towards Kane Basin. Region 39’s northern boundary extends north through the Kennedy Channel, arching north-west along the northern portion of the Ellesmere Island coastline. Continuing through the Arctic Ocean, the northern boundary arches south-west past Quttinirpaaq, extending just past Axel Heiberg Island.

Related links

- Find a national park

- Plan your visit

- Science and conservation

- Protecting species

- Research in national parks

- Creating new national parks

- Reservations

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

These Birds Have Their Own Beach. Their Human Neighbors Want In.

Every summer, a neighborhood in Queens loses its beach to piping plovers, an endangered shorebird. Some residents want it back.

By Hilary Howard

Sections of the Rockaway Peninsula, a coastal strip of land in southern Queens, look like beach towns more than the concrete and steel landscape of much of New York City.

On a mile-long stretch of the boardwalk in Edgemere, a neighborhood in the Rockaways that was a thriving resort destination a century ago, you can still see open skies, dunes and the ocean.

But for most of the summer, the beach here is closed.

Since 1996, this swath of sand and surf has been reserved for much of the spring and summer for nesting coastal piping plovers, which are endangered in New York and protected federally by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Along the Eastern Seaboard, from barrier islands to private and public beaches on the mainland, efforts are being made to provide safe habitats for them.

Some residents of Edgemere say the beach restrictions are unfair and further isolating for an area with a history of neglect that already lacks basics like a grocery store, a playground and reliable drainage on the often-flooded streets. Some are now asking if the beach can be shared during peak season with the surrounding community and leveraged for a revival of the neighborhood.

The grayish, brown and white birds, about seven inches in length, are at risk of extinction — about 6,000 currently live along the Atlantic Coast — because of human development, disturbances like vandalism and natural predators on the shoreline. (Plover species native to the Great Lakes and the northern Great Plains are also federally protected.)

The plover beach in Edgemere has evolved into a model of habitat preservation in an urban setting, drawing nature lovers from across New York. It is the only city-owned beach closed to the public and dedicated to plovers and other threatened shorebirds during their nesting season from April through August.

Sonia Moise, president of the area’s civic organization and a longtime resident, equates the lack of beach access with a lack of economic opportunity. Opening the beach, she argues, would bring in businesses and other services that would reinvigorate Edgemere. She has made it her mission to return the beach, or at least parts of it, to the neighborhood’s roughly 14,000 human residents, almost 90 percent of whom are Black or Hispanic.

The debate over beach access raises the broader issue of who should bear the burden of environmental stewardship. Historically, a lack of access to nature and the water has been pervasive in many poor communities and communities of color, said Bernice Rosenzweig, a professor of environmental science at Sarah Lawrence College.

And as climate change makes living along the coast more of a gamble, Dr. Rosenzweig said, people who live in Edgemere “face so many hazards from the water but don’t always get the benefits of living near the water.”

Many residents and local leaders said they believed a compromise could be reached where birds and people would share the beach during the summer.

“I believe we can coexist,” said Jackie Rogers, president of a community garden that in June hosted a Black Birders walk along with the N.Y.C. Plover Project , a nonprofit group based in the Rockaways that increases awareness about shorebirds.

Selvena Brooks-Powers, a member of the City Council who represents the area, said there was enough beach for the residents to enjoy while also protecting wildlife, but she emphasized that community beach access should be the priority.

Mel Julien, a local homeowner who does community outreach for the N.Y.C. Plover Project, has a more nuanced stance on coexistence.

“Sharing the shore doesn’t mean we share the exact same beach at all times,” she said. “Shorebirds need a head start, and for that, temporary beach closures are critical.”

Ultimately, the decision about beach access is up to the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, which owns and manages the area. But as the agency navigates budget cuts, a lifeguard shortage and a directive — established nearly 30 years ago — to protect the piping plovers, it has yet to find a solution that pleases all parties.

A department spokesman said the city was experimenting with opening parts of the beach earlier in the summer, once plovers and other shorebirds had left the area. If the birds were harmed, however, the department would be in violation of federal and state laws, he explained. (Earlier this month, roughly half of the plover beach reopened to pedestrians, the spokesman said)

“We are following federal guidelines,” Sue Donoghue, the parks commissioner, said, referring to norms for monitoring nesting plovers established by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “We take that responsibility very seriously.”

But there appears to be room for the city to relax its approach in Edgemere. Federal guidelines outline measures to protect nesting and chick rearing but do not specifically call for the closing of entire beaches. Rather, the onus is on local biologists and property managers to determine what works best on their sites, a spokesman for the Fish and Wildlife Service said.

What works best in the Rockaways can vary. The Breezy Point Cooperative, a community on the western section of the peninsula, keeps its beaches open and places fences around plover nests, while portions of the Rockaway beaches owned by the National Park Service are closed off from the dunes to the shoreline, though typically, these areas are both less than a mile long and not near densely populated neighborhoods.

Steve Sinkevich, a biologist with the Fish and Wildlife Service, singled out several other large beach closures during nesting season in New York, although those tend to be in dedicated nature refuges that are surrounded by water and where there is little to no housing.

Sara Zeigler, a research geographer with the United States Geological Survey, said the ideal situation for plovers and other shorebirds was “to nest along the beach and then move toward better foraging areas along inlets and the bay.”

But Edgemere, with its buildings, sidewalks and streets, can only safely offer its shoreline to the birds.

This explains why such a large part of it is closed to human activity during the summer. Plover chicks are the size of cotton balls and the color of sand, and are unable to fly, which means they are easy to step on. “If there are large numbers of patrons recreating along the ocean shoreline, plover chicks have nowhere else to forage,” Mr. Sinkevich said.

In the 20th century, Edgemere and Arverne, its neighbor to the west, went from glamorous vacation destinations — with beach bungalows and grand hotels — to a collection of barren lots, with several large public housing projects, built mostly in the 1950s, peppered throughout. By the late 1960s, the area was declared an urban renewal zone, and many buildings were razed to make way for new construction. But as city priorities shifted and, later, extreme weather like the Sandy superstorm hit the area hard, many development plans were thrown into limbo.

“As kids, we called it the forbidden zone,” said John Cori, who grew up in the Rockaways, worked for the parks department in Edgemere in the 1980s and still lives nearby. “The boardwalk got so dilapidated because the beaches were underutilized.” Birds gravitated to Edgemere, he explained, because hardly any people did.

Still, its beach, though underused, was once open and had lifeguards, said Sonja Webber-Bey, a retired teacher and evaluator for the New York City public schools who moved to Edgemere in the 1970s.

Ms. Webber-Bey and her family enjoyed the beach and supported some of the development that had begun around them. But in the mid-1990s, the area’s seemingly single resource, the beach, closed. When she complained to local leaders, she said she was told that the parks department had decided that Edgemere was the best place for protecting the birds.

The area has played an important role in rebuilding the plover population, as well as those of other threatened shorebirds. Last year, 40 piping plover pairs — 80 birds — nested in the Rockaways, with 13 pairs in Edgemere, representing 33 percent of plovers on the peninsula, up from 36 pairs in the Rockaways and eight pairs in Edgemere nine years ago, Mr. Sinkevich said.

Since the agency introduced a recovery plan for piping plovers in the 1980s, the number of birds along the Atlantic coast has more than tripled, according to the Fish and Wildlife Service.

But whether residents in a dense city neighborhood should continue to stand down while their beach closes every summer for shorebird nesting is up for debate. “We are an endangered species, too,” said Ms. Brooks-Powers, the councilwoman. “Where’s our protection?”

Social Explorer, a demographic data firm, contributed research for this article.

Hilary Howard is a Times reporter covering how the New York City region is adapting to climate change and other environmental challenges. More about Hilary Howard

Around the New York Region

A look at life, culture, politics and more in new york, new jersey and connecticut..

Symbol of Despair and Hope: One block in Harlem has become a hub for drugs and disarray. Some see New York at its worst, while others see a community doing its best to help .

Piping Plover Takeover: Every summer, a neighborhood in Queens loses its beach to the endangered shorebird. Some residents want it back .

Broadway Turns to Influencers: To reach younger and more diverse audiences, Broadway shows are increasingly looking to Instagram and TikTok creators .

Street Wars: Eighth Avenue in Midtown Manhattan is a grand thoroughfare of vendors, tourists and commuters. It’s also crowded, dirty and sometimes dangerous .

Sunday Routine: The Reverend Vince Anderson, a mainstay of the Brooklyn music scene, fills his Sundays with worship in two languages, the Mets and a full hour of watering his 92 houseplants.

Search The Canadian Encyclopedia

Enter your search term

Why sign up?

Signing up enhances your TCE experience with the ability to save items to your personal reading list, and access the interactive map.

- MLA 8TH EDITION

- Slaymaker, Olav et al. "Physiographic Regions". The Canadian Encyclopedia , 29 April 2024, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/physiographic-regions. Accessed 11 August 2024.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , 29 April 2024, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/physiographic-regions. Accessed 11 August 2024." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- APA 6TH EDITION

- Slaymaker, O., & Acton, D., & Brookes, I., & French, H., & Ryder, J. (2024). Physiographic Regions. In The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/physiographic-regions

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/physiographic-regions" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- CHICAGO 17TH EDITION

- Slaymaker, Olav , and Donald F. Acton, , and I.a. Brookes, , and Hugh French, , and J.m. Ryder. "Physiographic Regions." The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published February 27, 2012; Last Edited April 29, 2024.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published February 27, 2012; Last Edited April 29, 2024." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- TURABIAN 8TH EDITION

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Physiographic Regions," by Olav Slaymaker, Donald F. Acton, I.a. Brookes, Hugh French, and J.m. Ryder, Accessed August 11, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/physiographic-regions

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Physiographic Regions," by Olav Slaymaker, Donald F. Acton, I.a. Brookes, Hugh French, and J.m. Ryder, Accessed August 11, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/physiographic-regions" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

Thank you for your submission

Our team will be reviewing your submission and get back to you with any further questions.

Thanks for contributing to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Physiographic Regions

Article by Olav Slaymaker , Donald F. Acton , I.a. Brookes , Hugh French , J.m. Ryder

Published Online February 27, 2012

Last Edited April 29, 2024